You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Glossary:

alveolar ridge—bony ridge of the mandible or maxilla

cao gao—oriental folk remedy in which coins are rubbed on the back or chest in the belief that the process will reduce fever

corroboration—support with evidence to make certain

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome—genetic disorder marked by easy bruising, scar formation, and tendency to bleed

epidermolysis bullosa—congenital skin disease characterized by the development of blisters, with or without provocation

hematologic—pertaining to the blood

hemophilia—hereditary blood defect characterized by delayed clotting and, in turn, difficulty in controlling hemorrhage even after minor injuries

idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura—condition of unknown origin exhibiting purplish spots on the skin or mucosa as a result of decreased numbers of blood platelets

Menke’s syndrome—hereditary disorder that in its severe form leads to mental retardation and early death

mucosa—mucous membrane, such as that covering the inside of the mouth

odontology—study of the anatomy, growth, and diseases of the teeth

orofacial—pertaining to the face and surrounding structures

P.A.N.D.A.—acronym for Prevent Abuse and Neglect through Dental Awareness

paruli—abscesses in the gum

pathognomonic—typical of a particular disease

perioral—surrounding the mouth

petechiae—small spot on a body surface, such as the skin or mucous membrane, caused by a very small hemorrhage

sequelae—condition that follows, especially one arising from a disease

Sturge-Weber syndrome—congenital disorder of unknown cause characterized by facial birth marks and eye irregularities

FAMILY VIOLENCE

Abuse and neglect have traditionally been discussed as affecting children. However, abuse and neglect can affect victims of any age. By definition, family violence can be the maltreatment of children (child abuse or neglect), competent adults (intimate partner violence or domestic violence), and senior citizens (elder abuse or neglect). The phrase “intimate partner violence” (IPV) is the current terminology describing abuse or neglect of those within or outside of a marriage who are above age 18 but not yet elderly. Such abuse also may involve partners of the same gender. At which age maltreatment becomes elder abuse or neglect is somewhat subjective, especially within an aging society focused on staying young. Despite a change in terminology, however, the physical signs of family violence are relatively consistent through time and may present in similar fashion in victims of any age.

CHILD ABUSE

Defined by state laws, the definition of child abuse varies somewhat from state to state. Statutes typically define child abuse as nonaccidental physical, sexual, or emotional injuries or trauma inflicted on a minor child by a parent or other caregiver.1 Child abuse can take many different forms and can present in different ways in the dental office. Child abuse includes those injuries inflicted by someone who has care, custody, and control of the child; it can include not only parents and guardians but also teachers, day care workers, and baby sitters. It does not include those considered “strangers.”

Data and Demographics

National statistics show that 3.7 million children were reported as abused or neglected in 2011, with 18.5% of those cases substantiated after investigation.2 A national study found that one child dies every 6 hours as a result of child abuse, and young children continue to be at highest risk for such fatalities. The number of child fatalities has varied over the past 5 years from a high of 1,685 in 2009 and a low of 1,545 in 2011. In 2011, approximately four fifths (81.6%) of the children who died were younger than age 4. Of these fatalities, 42.4% were younger than 1 year old.1-3

Child abuse and neglect know no boundaries. They are not limited to large cities, certain neighborhoods, or specific ethnic groups. Across the nation, cases of child abuse and neglect happen in all socioeconomic groups, and victims come from all ethnic groups. Cases also are spread out geographically, with victims in rural as well as urban settings. It is often said that every dental practice sees abused and neglected children. Unfortunately, these children are often not properly identified.

Etiology and Contributing Factors

First and foremost, dental care providers must remember that child abusers may love their children very much, even if they do not love their children very well. Abusers often are not motivated by hatred but rather by a warped sense of right and wrong in child rearing.

Child maltreatment undoubtedly can come from a breakdown in the parenting skills of the child’s caregivers. Many factors can lead to this failure of proper parenting. Child abuse and neglect may be one of many symptoms of a dysfunctional family.4 One theory holds that parents’ unrealistic expectations for the child and for themselves can contribute to the abuse. Another theory is that the abuser’s attitude toward children is based on the conviction that children exist to satisfy parental needs. For these parents, it follows that children who do not satisfy those needs should be physically punished in order to make them behave properly.5 Some mothers are simply not satisfied by the unresponsiveness and lack of feedback from an infant.3 One young mother’s tragic lament shows her self-justifying reasons for abusing her baby: “I’ve waited all these years for my baby, and when she was born she never did anything for me,” and “When she cried, it meant that she didn’t love me; so I hit her.”3

Other abusers explain the maltreatment of children as a suitable means of parenting. In one notable study, Dietrich et al interviewed abusers about their feelings subsequent to the abuse. Of those adults interviewed, 62.5% felt justified in injuring the child, 58.9% felt no remorse for their actions, and 50.7% blamed the victim for the abuse.6 Combining the three factors studied, fully one third of the adults interviewed felt justified, blamed the victim, and felt no remorse.6

It is well understood that several social factors contribute to child abuse, the most cited of which is substance abuse. Although substance abuse in and of itself does not cause family violence, it may make a bad situation worse. The abuse of alcohol or other drugs can be an indicator of other risk factors, including poverty, unemployment, depression, and feelings of hopelessness. Other common contributing factors are stress, lack of a family support network, and the cyclic problem of abuse as a learned behavior: Abusers are likely to have been abused as children. It has often been said that children who have been abused often grow up to abuse their own children, their spouse, and even their parents, a situation referred to as “retribution abuse.”

The Dental Team’s Involvement

Dental healthcare workers should be concerned about the rising incidence of child abuse and the lack of reporting by dental professionals. First of all, dentists in every state are mandated reporters; that is, they are required by law to report suspected cases of child abuse or neglect.1 Although dental assistants often spend more time with patients than their dentists, few states specifically require assistants to report suspected cases of abuse or neglect. Although state laws mandate such reports only from certain individuals, anyone can make a report.

Some facts about child abuse make it likely that most dental professionals will see it in their practice, even if they do not always recognize it. Multiple studies confirm that more than 50% and up to 75% of all child abuse cases involve trauma to the mouth, face, or head.7,8 Furthermore, while abusive parents often do not take the child to the same physician (fearing the physician will recognize the abuse), they tend to return to the same dentist.9 A 1995 national survey of child protective services agencies showed that dentists filed only 0.32% of all reports of suspected child abuse or neglect;10 no state tracks the number of dental hygienists or dental assistants making reports. According to Katner and Brown in the October 2012 issue of JADA, most dentists are still not reporting.11 Data from various states show that the vast majority of reports come from teachers, social workers, and “permissive reporters” (those individuals who are not required to report but do so out of concern for the child).

Few dental professionals recognize family violence as something their patient may encounter. One study found that dentists (N = 247) and hygienists (N = 271) were least likely to suspect abuse and did not view themselves as responsible for dealing with abuse situations.8 If dental professionals are in the best position to see some injuries from child abuse, why don’t they recognize them? If they suspect the abuse, why don’t they report it? One answer may be that they fear it will alienate their paying patients, or they fear retaliation lawsuits from the parents.12

Clinical Protocol

Every dental office needs a protocol to raise awareness of symptoms of child abuse and neglect. Evaluate behavior and histories, and conduct a general physical assessment along with the oral examination. The warning signs of abuse should be in the back of all dental workers’ minds each time they see an injured patient. Repeated injuries, multiple bruises, bilateral injuries to the face, or injuries that are inconsistent with the history given may all signal instances of abuse.

Behavior assessment is just one part of the patient evaluation. Dental assistants often spend the most time with a child during a dental visit and may be in the best position to evaluate behaviors. Abused or neglected children may be extremely apprehensive and inordinately fearful of an oral examination. On the other hand, some abuse victims are extremely eager to please; they have learned that less than perfect behavior may result in more abuse. One way to determine if a child’s behavior is appropriate is to judge against personal experience with children of a similar maturity (note that maturity is often different from chronological age) in similar circumstances. Share your impressions with the dentist. Combining your evaluation of the child’s behavior with other information in the patient history and with the dentist’s oral examination may lead the dentist to suspect child abuse.

It is always best to obtain histories of an injury from the child and adult separately, although abusers may not want you to be alone with the child. If dental radiographic images are indicated, x-raying the child alone provides an opportunity for a private conversation. Never take radiographic images merely as an excuse to have the adult leave the operatory. Taking unauthorized or inappropriate radiographic images may constitute technical battery and open the dentist or assistant to liability.

Review the adult’s and child’s versions of the history and determine if any discrepancies exist in how and when the injuries occurred. Also determine if the injuries are consistent with the explanations. Be sure to have the dentist document in the patient chart any discrepancies in the stories given and note any physical findings that are inconsistent with the history provided.

Common Presentations of Accidental Injuries, Predisposing Medical Conditions, and Other Causes

Accidental injuries, predisposing medical conditions, and other causes may mimic symptoms of abuse. Be aware that children receive normal bumps and bruises in accidents. Foreheads, chins, hands, feet, elbows, and knees are the most typical sites for accidental injuries in childhood accidents. However, children can get hurt anywhere on their bodies and apparently in an infinite number of ways. Always use clinical judgment to weigh the facts and the presenting symptoms.

As with accidental injuries, many otherwise normal conditions exist that may mimic child abuse injuries. A thorough health history, updated regularly, will help clinicians make a proper diagnosis. Bleeding disorders such as hemophilia and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura make children more susceptible to bruising. If these patients are not adequately treated through hematologic therapies, they bruise easily and sometime bruise spontaneously.

Conditions that cause discoloration of a child’s skin, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome, Mongolian spots (also known as the slate-gray spots of infancy), or even simple birth marks can be confused with abuse injuries. While these types of marks may eventually fade with time, they are essentially permanent discolorations.

Some folk medicine remedies also cause marks similar to abuse. Cao gao, or oriental coin rubbing, can cause extensive bruising to the skin. “Cupping,” a practice from Central and South America where hot ceramic cups are placed on the skin to draw out fever, causes round suction marks on skin. A more modern version of cupping involves plastic cups and a hand-operated pump. None of these practices is meant to harm the child but are felt in some cultures to be suitable therapy for children’s illnesses. All clinicians must be familiar with the cultural diversity of their patients and understand these practices.

Other, more rare conditions may also mimic child abuse. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects collagen formation, may present with numerous marks that resemble multiple bruises. Epidermolysis bullosa, an autoimmune disorder, may mimic burns that are healing. Children with Menkes syndrome may have brittle hair that resembles traumatic hair loss. Again, a good health history helps clinicians to differentiate these conditions from abuse injuries.

Common Presentations of Injuries from Abuse

Bruises or welts, however, may indicate abuse. Be concerned about injuries to the face, lips, mouth, and neck as well as any to the ankles or wrists that may be visible in the course of a normal dental visit. Injuries to both eyes or cheeks are always suspicious because accidents are most typically unilateral. (It is rare, although not impossible, to fall down and hit both sides of your face.) Bilateral injuries of abuse also can occur on other easily observable areas of the child’s body.

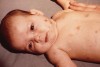

Injuries that form a pattern are also suspicious. A slap with an open hand can leave marks indicative of the abuser’s fingers (Figure 1). “Grab-marks” on arms or shoulders may indicate excessive force in punishing a child (Figure 2).

Burns are a common occurrence in life but certain burns should make you think twice about possible abuse. Cigar or cigarette burns on the palms of the hands or elsewhere, or multiple circular burn marks should be a red flag during physical assessment (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Immersion burns by scalding water can produce a sock-like or glove-like pattern on hands and feet (Figure 5). Patterned burns from hot objects such as a radiator, floor furnace, or a hot implement are often easy to identify; the difficulty, however, lies in determining if the burn is accidental or nonaccidental.

All these injuries must be considered in light of the fact that all children get hurt from time to time. Important information for analyzing bruises is knowing the color changes that occur during healing. Individual healing may differ markedly, and the appearance of bruises may differ based on the amount of trauma incurred. However, evaluating the color of a bruise may help you determine if the history you have received coincides with the actual date of the injury (Table 1). Clinicians without extensive forensic background are cautioned against trying to date the actual occurrence of trauma. Use the colors of healing as guidelines to assess whether the stated history matches the symptoms seen. Consider that bruises that are still swollen, red, blue, or purple are new. Bruises that present as yellow, green, or brown are older. Be most concerned if the history given contends that the injury happened in the past 24 hours but the marks are obviously many days or weeks old. Delay in seeking treatment is often seen in cases of family violence.

Evaluate dental or facial injuries carefully to determine their cause. Although the injuries of child abuse are many and varied, several types of injuries are common to abuse. Many of these injuries are within the scope of dentistry or easily observed in the course of routine dental treatment. Other types of injuries are pathognomonic to child abuse and easily identified by the dentist. Injuries of this type include those that appear simultaneously on multiple body planes3 (Figure 6). Injuries that exhibit patterned marks of implements or the adult’s hand or bilateral injuries to the face (Figure 7) carry a high index of suspicion of abuse.13

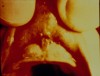

Even cases of child sexual abuse may exhibit indicators in the perioral region. Oral or perioral lesions of gonorrhea, syphilis, or chlamydia in prepuberal children are indicative of sexual abuse.14 In addition, petechiae of the hard or soft palate are sometimes seen in cases of forced oral sex (Figure 8). Other indicators of possible child abuse may include pain or difficulty in walking or sitting, pregnancy in young children, and extreme fear of any dental treatment. Of course, not everyone who is afraid of dental treatment is a victim of child sexual abuse. Because of their history of abuse, however, victims of an oral rape can be terrorized by having something as benign as a mirror or explorer placed in their mouths.

The head and face are often attacked in child abuse because they represent the “self” of the child. Some such injuries of child abuse are a matter of convenience: The child’s head may be the easiest place for an adult to reach. In other cases, the mouth is often injured due to the abuser’s desire to silence a crying child.15 Surveys of dentists who have reported cases to child protective agencies show a trend in the type of oral injuries encountered in child abuse cases. In a survey of pediatric dentists throughout the nation, the principal dental injuries reported in cases of child abuse included missing and fractured teeth (32% of reported cases) (Figure 9), oral bruises (24%), oral lacerations (14%) (Figure 10), jaw fractures (11%), and oral burns (5%).16,17 Although the sample size of this study was limited, pediatric dentists may be more likely to encounter more child victims due to the focus of their practices.

Even the youngest victims of abuse can have oral injuries. Lacerations and contusions of the oral mucosa, particularly around the anterior alveolar ridge, are seen in cases of forced feeding when the bottle is shoved forcefully against a child’s mouth (Figure 11).5 In older children, gags used to silence or punish a child can leave bruises at the corners of the mouth.18,19

Always be wary of human bite marks on a child. Human bite marks, which should be easily identifiable by all dental professionals, carry a high index of suspicion of child abuse.20 Human bites tend to compress the flesh, while animal bites are more likely to tear it (Figure 12). Also be aware of the differences between animal and human dentition and arch forms to properly identify the cause of a mark. Actual identification of the perpetrator through bite mark analysis is left to experts in forensic odontology.

Every member of the dental team should be able to see most abuse-related bite marks. Forty-three percent of all abuse bite marks are located on the head and neck,21 and 65% of these marks can be seen while the child is clothed.22 Human bites are painful and represent an assault with a weapon that carries a significant possibility of morbidity or even mortality. The infection potential of the human bite is significant and serious.

CHILD NEGLECT

Child neglect also is a huge problem. For every case of child abuse, an estimated 10 children are neglected. Unfortunately, children without adequate dental care are seen in dental offices every day. As such, states have provided a definition of child neglect to help differentiate it from simple lack of care.

Although state definitions of neglect vary considerably, all specify acts of omission, including failure to provide adequate care, support, nutrition, shelter, and medical or other care necessary for a child’s health and well being.1 Parents who cannot access or finance dental care may not be neglecting their children. However, if resources are available and the child is not receiving proper care, a suspected case of neglect should be reported (Figure 13). According to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, “dental neglect is a willing failure of parent or guardian to seek and follow through with treatment necessary to ensure a level of oral health essential for adequate function and freedom from pain and infection.”23 Because neglect may involve many factors, including money, insurance, transportation, and access to care, deciding to report suspected neglect may take more consideration than a suspected abuse case.

Questions often arise as to when missed dental appointments should raise suspicion of child neglect. Because state statutes provide no guidelines for when these cases should be reported, dental team members must carefully evaluate the seriousness of the child’s untreated condition, the family’s resources, and factors affecting access to care before deciding to make a report. Where one case may not need to be reported even after two or three missed appointments, another case may require a report after just a single broken appointment if the child is in imminent danger of serious physical sequelae from lack of care.

INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, IPV is defined as abuse that occurs between two people in a close relationship. The term “intimate partner” includes current and former spouses and dating partners. IPV exists along a continuum from a single episode of violence to ongoing battering.

IPV includes four types of behavior:

• Physical abuse is when a person hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, burning, or other physical force.

• Sexual abuse is forcing a partner to take part in a sex act when the partner does not consent.

• Threats of physical or sexual abuse include the use of words, gestures, weapons, or other means to communicate the intent to cause harm.

• Emotional abuse is threatening a partner or his or her possessions or loved ones, or harming a partner’s sense of self-worth. Examples are stalking, name-calling, intimidation, or not letting a partner see friends and family.

As is also found in elder abuse and neglect, the physical and behavioral signs of intimate partner violence are often quite similar to the signs of child maltreatment.

REPORTING SUSPECTED ABUSE OR MALTREATMENT

Children

Before making the report, a decision must be made whether a dental professional should visit with the parent or caregiver regarding the child’s condition. If it is in the child’s best interests to speak with the adult before making a report, the dentist should speak with the adult in private but with another member of the staff present as a witness. In that confidential setting, the dentist should express a concern for children in general and for the particular child specifically, unemotionally stating the requirement to report suspected abuse and neglect and relating the conditions, behavior, or history that raised his or her concerns. Avoid being judgmental. Even if the child is a victim, it may not be at the hands of the adult present, and the maltreatment may be totally unknown to the person receiving the information.

Dentists and dental staff are not the professionals charged with determining whether abuse or neglect has actually occurred. Their responsibility is only to report suspected cases. Dental assistants should talk privately to the dentist and other staff members about conditions or problems they see. It may be beneficial, but is not mandatory, for the dentist to consult with the child’s physician to discuss any concerns. The physician may have useful information about the child’s condition and medical history.

If a report needs to be made, make the report immediately, or have the dentist make the report immediately. Simply call the state or local child protective agency, as dictated by state law. A trained social worker will discuss the case with you and determine necessary action. It should be noted that a call to a child protective agency does not necessarily mean you have to file a report on the specific case. The call can be a professional consultation to help you decide if you need to report. Most importantly, remember that a call to a child protective agency is not an accusation but a request for help on behalf of a child. If an investigation is warranted, the agency will investigate the case.

Based on its investigation, the agency will determine if a case is “substantiated,” meaning that credible evidence was found to indicate abuse or neglect, or if it is “unfounded,” which means that insufficient evidence exists to substantiate maltreatment. Even if a case is deemed unfounded, a child may still be at risk. If sufficient evidence was not found, information from the initial inquiry may be useful in future investigations to benefit the child.

Liability is not an issue in reporting suspected abuse or neglect. State laws contain language that protects mandated reporters from criminal and civil liability arising from good-faith reports. Unfortunately, dental workers can still be sued for making a good-faith report. Unless bad faith is proven, however, they cannot be held liable. The reality of modern American society is that anyone can be sued for any reason. Nonetheless, in reporting suspected child maltreatment, such suits generally have no foundation in law.

Privileged communication does not apply to suspected child abuse or neglect cases. The law states that privileged communication between a professional person and his patient does not apply to situations involving abused or neglected children, and does not constitute grounds for failure to report as required.9 Information given to the dentist by a patient may be shared with the child protective agency in the investigation of child abuse or neglect, and doctor–patient privilege is not a valid excuse for failing to report a suspected case.

Although all 50 states require dentists to report, there is also a provision for civil and criminal penalties for failing to report suspected cases, and in some states, the loss of their licenses.12,24 It is important for mandated healthcare professionals to note that malpractice insurance does not cover criminal acts. Because failure to report can be a crime, injuries resulting from such failure might expose a healthcare professional to uninsured professional liability.1

Adults and the Elderly

States that mandate healthcare professionals to report suspected child abuse and neglect also mandate reporting of suspected elder abuse and neglect. As with child maltreatment, the definition of elder abuse, or maltreatment of “endangered adults,” varies from state to state.

Most states have requirements for mandatory reporting of institutionalized adults in hospitals, nursing homes, or other long-term care facilities. However, few states require reporting of otherwise competent adults who are victims of intimate partner violence. Mandatory reporting of adults compromises patient confidentiality, creates a less safe situation for victims, and removes individual autonomy. Because the most dangerous situation for an abused spouse is when she or he tries to leave, mandatory reporting can actually increase the risk of serious injury or death.

According to Futures Without Violence (formerly the Family Violence Prevention Fund), only five states require licensed healthcare professionals to report suspected “domestic violence” or “intimate partner violence.”25 Although a difference of opinion on mandatory reporting of adults certainly exists, it is widely known that mandatory reporting of IPV can put the victim at great risk.

Because of wide variation in statutory language, dental professionals must be knowledgeable about reporting requirements in the state(s) where they work. Even where reporting of suspected IPV is not required, all dental professionals should be educated about other appropriate intervention. Routine inquiry of all women of child-bearing age should be part of the routine intake and recall history. In private, all patients should be asked if they have ever been hit, kicked, punched, or frightened by someone important to them. A more succinct question is to ask “how are things at home” known as “HATAH.” Sometimes it is sufficient to merely ask the patient if it is safe to go home.

Given a suspicion of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, dental professionals should be prepared to support the victim by stating that no one deserves to be a victim of family violence, that violence is not the fault of the victim, and that resources are available. Everyone in the dental office should be aware of local resources that can include shelters and safe houses. Contact your state Coalition Against Domestic Violence before the situation arises, to learn about what is available in your community.

INTERVENTIONS

State and local programs have had remarkable success in raising awareness about family violence. In 1991, an effort in Massachusetts led to what has become arguably the most successful program to get dentists involved in family violence prevention. In that year, several Massachusetts organizations formed what was then known as the Dental Coalition to Combat Child Abuse and Neglect. The idea spread to Missouri where various dental organizations joined together to form the Prevent Abuse and Neglect through Dental Awareness (P.A.N.D.A.) coalition.

The mission of the P.A.N.D.A. coalitions is to create an atmosphere of understanding in the healthcare community that will result in the prevention of abuse and neglect through early identification and appropriate intervention for any persons who have been abused or neglected.25 To accomplish that goal, the coalition produced a series of educational programs to present to dentists, hygienists, and assistants, as well as to dental and dental hygiene students. Within its first year, Missouri’s P.A.N.D.A. spokesperson traveled the state, making presentations to every dental society, dental study club, and dental hygiene group in Missouri.

P.A.N.D.A.’s success is also spurred on by its choice of acronym and mascot. The picture of the P.A.N.D.A. became the backdrop for all of the coalition’s programs. The P.A.N.D.A. became a perfect symbol for the coalition’s work. It is endangered, just like victims of abuse and neglect. Also, with permanent “black eyes,” the P.A.N.D.A. serves as the perfect reminder of the injuries often resulting from abuse (Figure 14 and Figure 15).

While the group’s early efforts concentrated on continuing dental education seminars, they quickly expanded into a much broader program. At the urging of coalition members, child abuse and family violence prevention were added to the curriculum of the state’s dental school and dental hygiene programs. The coalition further refined its presentations for medical seminars, nursing groups, teachers, day care workers, and other lay organizations. As it conforms to the needs of the various groups it educates, P.A.N.D.A. also continually addresses changes in policy and state laws.

The original coalition was fortunate in one other area that helped ensure its success. In 1992, Missouri was one of only six states that tracked the number of dentists reporting child abuse and neglect. Starting with a minuscule percentage of reports from dentists, the reporting rate by Missouri’s dentists rose 60% in the first year of the P.A.N.D.A. educational programs.26 Within the first 3 years, reporting had climbed by 160%.27 At the urging of P.A.N.D.A. coalitions, three additional states now track dentists’ reporting data, and improvements as high as 800% have been seen in as little as 5 years. The ultimate goal of these efforts is to involve more people until eventually fewer cases of family violence need to be reported.

Although dentists are mandated reporters of child abuse and neglect in every state,1 only 18 states at the time of the 1995 national survey had any formal training protocol for any mandated reporters.10 This failure leaves dentists and other mandated reporters in the unfortunate position of having no formal training to help diagnose the cases they are required to report. It is not unusual to find low reporting rates, considering the dearth of education for reporters.

While the increased rate of reporting by dentists is one measure of success, another is the replication of the P.A.N.D.A. program in other state and international settings. Currently, 46 states have P.A.N.D.A. programs, with varying levels of activity. Coalitions are also in place in Ontario, Canada; Timisoara and Turnu Severin, Romania; Guam; Finland; Israel; Peru; Brazil; and worldwide as part of the US Army Dental Command. P.A.N.D.A.’s founders are working with individuals and organizations in the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia as well as in Belgium, South Africa, Mexico, and India. Other states and nations also are forming coalitions as the P.A.N.D.A. family continues to grow.

Although the P.A.N.D.A. program began by concentrating on children’s issues, the broader issue of family violence affects victims of all ages. As with child abuse injuries, the other forms of family violence (domestic violence and elder abuse) also are most likely to involve injuries to the head and neck.28 Therefore, P.A.N.D.A. has added information on intimate partner violence (variously known as violence against women, spousal abuse, and domestic violence) and elder abuse and neglect to its message. Its mission statement has been refined in many states to reflect that the coalition encourages “appropriate intervention” for suspected family violence victims of any age.

SUMMARY

Abuse and neglect are growing at ever-increasing rates in the United States. It is not only within the purview of dental practice to identify and report suspected cases, it is also required under state laws. An appropriate child abuse and neglect protocol in the dental practice may be the best defense for children in these unfortunate situations. Discuss family violence at staff meetings. Be aware of the warning signs, know what to consider when you see an injury, and know how to report suspected cases.

When you see a patient who may be a victim, remember that everyone else in the dental office has seen the same patient and may have useful information. Talk privately among yourselves about what you see and hear. Encourage the dentist to fulfill his or her legal obligation by reporting suspected cases as dictated by state law, and understand that anyone can report child maltreatment, whether specified as a mandated reporter or not. Remember that breaking the cycle of abuse and neglect not only can make your patient happier and healthier, it also may save a life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Mouden is the founding father of the P.A.N.D.A. (Prevent Abuse and Neglect through Dental Awareness) coalition. He is an internationally recognized author and lecturer on the clinical and legal aspects of child abuse and family violence prevention. He earned his dental degree with distinction from the University of Missouri at Kansas City, and his masters degree in public health from the University of North Carolina. After 16 years in private practice, 8 years with the Missouri Department of Health, and 12 years as the director of Arkansas’ Office of Oral Health, he now serves as the chief dental officer for the Federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. He also holds faculty appointments as associate clinical professor at the UMKC School of Dentistry, adjunct clinical assistant professor in the UAMS College of Medicine, associate professor in the UAMS College of Health Related Professions, and professor in the UAMS Fay W. Boosman College of Public Health. Dr. Mouden also serves as the American Dental Association Expert Spokesperson on Family Violence Prevention and is a consultant to the ADA’s Council on Access, Prevention, and Interprofessional Relations. For more information on P.A.N.D.A., contact Dr. Mouden via e-mail at Lynn.Mouden@cms.hhs.gov.

REFERENCES

1. Mouden LD, Bross DC. Legal issues affecting dentistry’s role in preventing child abuse and neglect. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1173-1180.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2011. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm11.pdf#page=28. Accessed July 8, 2014.

3. Schmitt BD, Kempe CH. The pediatrician’s role in child abuse and neglect. Current Problems in Pediatrics. 1975;5(5):1-47.

4. American Medical Association. Council on Scientific Affairs. AMA diagnostic and treatment guidelines concerning child abuse and neglect. JAMA. 1985;254(6):796-800.

5. Kempe CH. Paediatric implications of the battered baby syndrome. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1971;46(245):28-37.

6. Dietrich D, Berkowitz L, Kadushin A, McGloin J. Some factors influencing abusers’ justification of their child abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14(3):337-345.

7. daFonesca MA, Feigal RJ, ten Bensel RW. Dental aspects of 1248 cases of child maltreatment on file at a major county hospital. Pediatr Dent. 1992;14(3):152-157.

8. Little K. Family Violence: An Intervention Model for Dental Professionals. OVC Bulletin. December 2004. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/ovc/publications/bulletins/dentalproviders/message.html. Accessed July 7, 2014.

9. Becker DB, Needleman HL, Kotelchuck M. Child abuse and dentistry: orofacial trauma and its recognition by dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97(1):24-28.

10. Mouden LD. A National Survey of Dentists’ Reporting of Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect. Conducted by the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors for the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, US Department of Health and Human Services. Contract no. 140759. Unpublished data.

11. Katner DR, Brown CE. Mandatory reporting of oral injuries indicating possible child abuse. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:1087-1092.

12. Harrison L. Many dentists may violate child abuse reporting laws. Medscape Medical News. Oct. 11, 2012. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/772499. Accessed July 8, 2014.

13. Mouden LD, Lowe JW, Dixit UB. How to recognize situations that suggest abuse/neglect. Missouri Dental Journal. 1992;72(6):26-29.

14. Shanel-Hogan K. Reporting child abuse and neglect: responding to a cry for help. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1999;27:869-879.

15. Vadiakas G, Roberts MW, Dilley DC. Child abuse and neglect: ethical and legal issues for dentistry. J Mass Dent Soc. 1991;40(1):13-15.

16. Malecz RE. Child abuse, its relationship to pedodontics: a survey. ASDC J Dent Child. 1979;46(3):193-194.

17. Shanel-Hogan KA. What is this red mark? J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32:304-305.

18. McNeese MC. When to suspect child abuse. American Family Physician. 1982;25(6):190-197.

19. Saxe MD, McCourt JW. Child abuse: a survey of ASDC members and a diagnostic-data-assessment for dentists. ASDC J Dent Child. 1991;58:361-366.

20. Leung AKC, Robson WLM. Human bites in children. Pediatric Emergency Care. 1992;8(5):255-257.

21. Rawson RD. Child abuse identification. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1986;14(3):22.

22. Blain SM, Kittle PE. Child abuse and neglect—dentistry’s intervention. Update Pediatr Dent. 1989;2(2):1-7.

23. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. AAPD Reference Manual. Chicago, IL; 1997.

24. Mouden LD. The role for dental professionals in preventing child abuse and neglect. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998;26:737-743.

25. Hyman A for the Family Violence Prevention Fund. Mandatory Reporting of Domestic Violence by Health Care Providers: A Policy Paper. November 3, 1997; Family Violence Prevention Fund, San Francisco, CA.

26. Mouden LD. The role Tennessee’s dentists must play in preventing child abuse and neglect. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 1994;74(2):17-21.

27. Missouri Department of Social Services, Division of Family Services. Child Abuse and Neglect in Missouri: Report for Calendar Year 1996. April 1997; Jefferson City, MO: Missouri Department of Social Services.

28. Berrios DC, Grady D. Domestic violence: risk factors and outcomes. West J Med. 1991;155(2):133-5.

Appendix: Office Protocol for Identifying and Reporting Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect

Steps in Identification of Suspected Abuse or Neglect

1. General physical assessment of the patient. Although general physical examinations may not be appropriate in the dental setting, be aware of obvious physical traits that may indicate abuse or neglect (eg, difficulty in walking or sitting, physical signs that may be consistent with the use of force.)

2. Behavior assessment. Judge the patient’s behavior against the demeanor of patients of similar maturity in similar situations.

3. Health histories. If you suspect child maltreatment, it can be useful to obtain more than one history; one from the child and one separately from the adult.

4. Orofacial examination. Look for signs of violence, such as multiple injuries or bruises, injuries in different stages of healing, or oral signs of sexually transmitted diseases.

5. Consultation. If indicated, consult with the patient’s physician about the patient’s needs or your suspicions.

Steps in Reporting Suspected Child or Elder Abuse or Neglect

1. Documentation. Carefully document any findings of suspected abuse or neglect in the patient’s record.

2. Additional witness. Have another individual witness the examination as well as note and co-sign the records concerning suspected abuse or neglect.

3. Reporting. Call the appropriate child or adult protective services (CPS or APS) or law enforcement agency in your area, consistent with state law. Make the report as soon as possible without compromising the patient’s dental care.

4. Necessary information. When making the report, have the following information at hand:

• Name and address of the patient and parents or other persons having care and custody of the child

• Patient’s age

• Name(s) of the child’s sibling(s)

• Nature of the patient’s condition, including any evidence of previous injuries or disabilities

• Any other information you believe might be helpful in establishing the cause of the abuse or neglect as well as the identity of the person believed to have caused such abuse or neglect.

Adapted from Lynn Douglas Mouden, DDS, MPH; e-mail: Lynn.Mouden@cms.hss.gov