You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

GLOSSARY

Anomaly ─ Irregularity; deviation from normal.

Arthritis ─ Inflammation of a joint, usually accompanied by pain, swelling, and frequently changes in structure.

Asthma ─ A disorder of respiration marked by labored breathing.

Bacterial endocarditis ─ An infection of either the heart’s inner lining or the heart valves, caused by bacteria usually found in the mouth, intestinal tract, or urinary tract.

Cerebral palsy ─ A group of problems that affects body movement and posture. It is related to a brain injury or to problems with brain growth, causing reflex movements that a person cannot control and muscle tightness that may affect parts or all of the body.

Chronic ─ Of long duration; designating a disease showing little change or of slow progression; opposite of acute.

Contraindications ─ Any symptom or circumstance indicating the inappropriateness of a form of treatment otherwise advisable.

Epilepsy ─ Convulsive disorder characterized by muscular spasms and loss of consciousness.

Malocclusion ─ A misalignment of teeth and/or incorrect relation between the teeth of the two dental arches.

Multiple sclerosis ─ An inflammatory disease of the central nervous system.

Muscular dystrophy ─ Wasting away and atrophy of muscles.

Orthopedic ─ Prevention or correction of deformities.

Orthopedics ─ Branch of medicine dealing with the surgery of bones and joints.

Paralysis ─ Loss of the power of movement or sensation in one or more parts of the body.

Spasticity ─ Sustained increased muscle tension.

Spina bifida ─ Condition in which there is a defect in the development of the spinal column.

DEFINING DISABILITIES

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1992 defines a disability “as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities such as caring for one’s self, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning, and working.” Several conditions that may allow one to qualify as disabled are orthopedic, visual, speech and hearing impairments, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, mental retardation, and specific learning disabilities. Less obvious impairments include epilepsy, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, emotional illness, drug addiction, and alcoholism.1

Developmental disabilities occur during the period when most body systems of a child are developing before birth, at birth, or before the age of 22 years and usually last a lifetime. Those with developmental disabilities often have several impairments and may have limitations in learning, communication, and living independently. Cerebral palsy and mental retardation are examples of developmental disabilities. Acquired disabilities are the result of disease, trauma, or injury to the body and include spinal cord paralysis, limb amputation, and arthritis.2 Both categories of disabilities may require the aid of a caregiver.

When providing dental care for individuals with disabilities, the dental healthcare team is treating “patients with special needs.” The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA), a branch of the ADA responsible for setting the standards for dental education, defines special needs patients as “those patients whose medical, physical, psychological, or social situations make it necessary to modify normal dental routines in order to provide dental treatment for that individual...people with developmental disabilities, complex medical problems, and significant physical limitations.”3

STATISTICS

What do these statistics mean to dental professionals and the populations we serve? There are currently 54 million people in the United States living with some type of disability (Table 1).4 Seventeen percent of children under 18 have a developmental disability. In 2000, US births included:

• 12,500 children with cerebral palsy

• 5,000 children with hearing loss

• 4,400 children with vision impairment

• 800 children with spina bifida

• 3,300 children with cleft lip/palate

• 8,600 children with a variety of musculoskeletal anomalies3

Severe disabilities become more common with age. The Census Bureau reports that 38% of those age 65 years and older have a severe disability. As the baby boomer generation (those born between 1946 and 1964) ages, the numbers become even more significant; experts estimate that by 2030 one in five Americans will be 65 years of age.5

DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION

Many disabled individuals living in the community with their families are treated in private dental practices. Over the past 40 years changes in social policies and legislation have led to a dramatic decrease in individuals with developmental disabilities residing in state-run institutions. In addition, many facilities have closed. Medical and dental care was provided on a routine basis within the institution. Deinstitutionalization has not only mainstreamed many into group residential homes or at home with their own families but also has disrupted the continuum of their care. As a consequence, they are dependent upon the private dental practice for needed dental services.4 By providing needed care, the dental team can contribute to the oral health, overall wellness and personal self-esteem of a patient with a disability. The main objectives of care are:

• to motivate the patient and caregiver to maintain oral health;

• prevent infection and tooth loss;

• prevent the need for extensive treatment that patients may not be able to tolerate due to their physical or mental condition; and

• make appointments pleasant and comfortable.14

ORAL HEALTH AND THE DISABLED

According to former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, MD, “You are not healthy without good oral health.”6 The link between oral health and systemic health has shown that many systemic diseases and medical treatments have oral health implications. Poor oral health has an impact on learning, communication, self-esteem, and nutrition which affects activities in school, work, and home. The prevalence and severity of caries and periodontal disease in the disabled population is significantly higher than the rest of the population. The chronic nature of dental disease makes this fact even more important when thinking of patients with special needs who already may have a lifetime of compromised oral and physical health.7 Poor oral hygiene due to lack of ability for self-care may have serious health implications in persons with disabilities. Inflammation present in periodontal disease has been linked to cardiovascular disease while oral infection may cause bacterial endocarditis in susceptible patients with cardiac defects. Poor oral hygiene can also place a person at risk for pulmonary infection and lung disease.8

Oral health starts in childhood. It is important for children with special needs to have healthy teeth and gingiva to aid in speech development and allow the child to chew a wider variety of foods.9 Some disorders can cause anomalies or variations in the eruption, number, size, and shape of teeth (Figure 1). Malocclusion is a frequent occurrence (Figure 2). Developmental defects from high fever or medications can create under-mineralized, decay-prone enamel (Figure 3). Oral trauma to the face and mouth occur more frequently for those who have poor muscle coordination or seizures (Figure 4).10 Poor motor coordination inhibits the natural cleansing ability of the tongue, lips, and cheeks and hinders brushing and flossing. Habits such as pocketing food in the cheeks and mouth breathing also compromises self-cleansing abilities.5 Special diets of pureed foods stick to the teeth and medications sweetened with syrup or sugar contribute to tooth decay. Several problems are caused by drugs used to treat the disability. Anti-seizure medications cause gingival overgrowth, known as gingival hyperplasia, resulting in interference with chewing and speech, gingival bleeding, and periodontal disease. Sedative drugs used for muscle control may reduce the flow of saliva that protects the teeth. Children and adults with a mental disability may not be able to express themselves or do not understand the importance of daily oral hygiene. Many rely on caregivers who themselves do not understand the importance of oral health. Informed caregivers make the job easier for dental professionals.9,10

Older adult disabilities add complications to the normal aging process. This fact is significant when we consider that there has been a dramatic increase in the life expectancy of the disabled. “For example, in the 1960s the average life expectancy for a child with Down Syndrome was three to four years. Today it is 55 years, with many living into their sixties and seventies.”8 While children with disabilities often receive oral healthcare in specialty pediatric practices, as they become adults their care ends when they “age out” of these practices.11 The chronic problems of aging such as heart disease, lung disorders, arthritis, and type II diabetes may manifest themselves 15 to 20 years sooner in the person with disabilities. The oral health of a younger disabled adult may be similar to the level of oral health in a person much older without disabilities. For many adults, oral problems experienced in childhood may have never been fully addressed. Decayed roots, adult periodontitis, missing teeth, and tooth replacement create an added burden to what already exists.12

SPECIAL CARE DENTISTRY (SCD)

“Special care dentistry is the delivery of dental care tailored to the individual needs of patients who have disabling medical conditions or mental or psychological limitations that require consideration beyond routine approaches.”5 Patients with disabilities present with a wide range of conditions and level of impairment. SCD may be necessary for persons with severe movement disorders, chronic mental illness, persons who are adults in age but who function at a child’s level, and those with serious medical conditions who are at risk for adverse outcomes in the dental setting unless treated by a knowledgeable practitioner.15 For some people, SCD may be needed only at certain periods of life and not at others. Disabled persons who can express need and can access dental care on their own do not require SCD. In order to provide a tailored care plan to meet the needs of each individual patient, SCD requires a holistic view of oral health. Communication with all members of the healthcare team, family, caregiver, physician, social services, and the dental team is essential.16

The following questions will help each dental office assess preparedness to offer the needed services:

• Does the office have handicap access?

• Are members of the dental team comfortable or have experience with transferring patients to the dental chair?

• Is the dental health team familiar with the oral health problems faced by people with disabilities?

• Does the office have mouth props or supportive devices to aid patients who may have difficulties in opening their mouths?

• Is the dental health team knowledgeable about assistive devices to enable these patients to be more independent in managing their own oral hygiene?

• Are members of the dental healthcare team able to develop a personal oral hygiene program for an individual with intellectual/physical disabilities based on his or her level of understanding and ability?17

For many dental professionals the thought of accommodating these patients may at first seem overwhelming. Lack of experience, disruption of the office routine, need for special facilities and equipment, and inadequate compensation are perceptions that can be overcome. Some individuals with severe medical or movement problems may need to be treated in a hospital but those with mild or moderate disability can be treated in a private practice setting. Most procedures used for the general population can be applied to the patient with special needs. Some modifications to treatment may be necessary along with compassion and tolerance in each situation.

Creating a Barrier-Free Environment

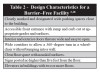

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1992 prohibits discrimination against a person with a disability who is seeking access to services, including dental services. Although the laws may vary by state, city, or county, the ADA sets standards and building codes for new construction to create barrier-free or universal design environments that make facilities and services usable by everyone. According to Title 3 of the law, the office is required to make modifications to an existing facility that allows access by persons with disabilities. Design characteristics for a Barrier-Free Facility are outlined in Table 2.2

Removal of barriers begins with a thorough evaluation of the physical office space. Simple changes need not be expensive, such as adding handrails to hallways and grab bars in restrooms, changing door knobs to a lever type, rearranging furniture in the reception area with various chair heights including space for a wheelchair, making magazine racks reachable, replacing high pile carpet with nonskid floor coverings, and eliminating hanging plants and area rugs. For easy entrance into the building the office can consider a portable ramp. The dental team can become active planners by asking patients for their input on how to make the office more accessible or by contacting local disability organizations for advice on a broad range of disabilities.18 Compliance information for new construction as well as regulations and checklists for removal of existing barriers are available at the Americans with Disabilities Act website (www.ada.gov).19

Assessment, Planning, and Appointment Scheduling

Most patients with a disability, or their caregivers, will be prepared to discuss treatment issues when they first contact the office to schedule an appointment. An accurate and current health history is essential. Depending on the disability and/or medical condition, a consultation with the patient’s physician, counselor, and other members of the rehabilitation team may be necessary to ensure treatment is safe and effective. Table 3 outlines issues and questions that will help the dental team members gather information that is vital for appointment scheduling and treatment planning.

Pretreatment planning helps to determine what preparation needs to be taken before the appointment. It may save valuable time, making the appointment a successful and positive experience for everyone. Forms can be mailed and filled out ahead of time. A phone interview can provide a disability profile detailing problems or limitations that impact care. For example, if the patient is using a wheelchair, what is the degree of mobility and will there be a need for help in transferring the patient to the dental chair? Does the patient need antibiotic premedication for treatment? Who will legally provide consent for treatment? What are the patient’s likes, dislikes, fears, and limitations?

Appointments may be dependent on transportation issues such as reserving special vehicles. There should be no conflict with bowel and bladder elimination, meals, or medicine schedules. For the young patient, naptime can be a consideration.

Dental care for the disabled patient will almost always take extra time and cannot be hurried. However, mobility and neuromuscular problems, mental capabilities, behavior problems, physical stamina, and sitting tolerance may require providing only a small amount of treatment at each visit. A mid-morning appointment may be the most ideal time. Persons with disabilities often need time to prepare for the visit, wait time is usually minimal, and early in the day the patient and the staff are at their best.14,20,21

Desensitization

Individuals with special needs may benefit from methods that help desensitize them to dental treatment. Before the visit family members or caregivers can familiarize the patient with oral care and a daily toothbrushing routine at home in familiar surroundings. Dental team members can instruct caregivers in proper technique to avoid any injury. Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate proper procedure allowing for head stabilization during toothbrushing.22

To reduce anxiety with strangers and unfamiliar environments, visits to the dental office before care begins may be helpful. Have the patient stop at the office during times other than routine office hours. Observing a family member receiving care in the treatment area may allow the patient to mimic desirable behavior. On the first visit for treatment, the patient can sit quietly in the chair with a family member or caregiver nearby to offer reassurance.

While relaxing in the chair, the patient’s teeth can be gently brushed to provide a positive experience. For the second visit, the team should follow the same routine. If the patient remains cooperative, a minor dental procedure such as a cleaning or a simple restoration can be performed.

If this process is successful more complex treatment may be gradually added. The dental team should continually monitor the patient’s behavior during each visit. If at any time the patient becomes uncooperative the appointment should be terminated for the day. If a restoration has been started and treatment must end, the practitioner can quickly place a temporary restoration allowing the procedure to be completed at a later time. If these methods are not successful, dental procedures may have to be completed using sedation and/or protective stabilization.20,21

Protective Body Stabilization

Disabled patients frequently have problems with support, balance, and even aggressive behavior. Sudden involuntary body movements such as muscle spasms can be a danger to the patient and the dental team during treatment. Severe cases could require sedation or general anesthesia and hospitalization might then be appropriate.

In the office, stabilization may be used to make the patient feel comfortable and secure and allow for safe and effective delivery of quality care. Pillows, rolled blankets, or towels may be placed under the patient’s knees and neck to prevent muscle spasms and provide additional support. A beanbag chair placed on the dental chair will conform to the patient’s body while filling the space between the patient and the dental chair.

To minimize movement, a member of the dental team or caregiver may gently hold the patient’s arms and/or legs in a comfortable position. A team member can sit across from the operator and lightly place their arm across the patient’s upper body to keep the working field clear. A child may lay on top of a parent in the dental chair, with the parent’s arms around the child. This positioning should be monitored carefully because the parent can tire and easily lose control of the child during treatment.

An inexpensive method for stabilization is a bed sheet wrapped around a patient and secured with tape that can be easily cut if necessary. This approach may be less intimidating and even provide the patient with a sense of security. A commercially available medical immobilization device (MID) is illustrated in Figure 7. MIDs may be used for patients who have extreme spasticity, increased muscle tension, or severe behavioral problems. However, this method should not be considered for routine use.14,17,22,23

Mouth props may be necessary to provide care due to a lack of ability, or unwillingness to keep their mouth open. Use of a mouth prop not only provides protection from the patient suddenly closing their mouth but can also improve access and visibility for the dental team. Training on technique for safe use may be required. Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate commercially available devices.

A long piece of dental floss should be tied through the hole in a commercially available prop and extended outside the mouth for easy removal in case of a breathing problem. Inexpensive, easy-to-use mouth props can be readily assembled using materials in your office. One example is to tape together five wooden tongue depressors and fasten with waterproof tape. Then, wrap and tape several pieces of gauze around one end. To use, gently place the cushioned end between the teeth.

Another type of prop can be customized for the amount of bite opening desired. One end of a folded, moistened washcloth or several gauze squares folded together and moistened can serve to keep the mouth open. As with the commercial prop, some type of retrieval safety measure, such as a line of floss, must be incorporated. Precautions for the use of mouth props are outlined in Table 4.14,22,24

When considering the use of protective body stabilization, clinicians should be aware of the standards and regulations of their state’s Dental Practice Act. Additional education or a permit may be necessary in some states.

The dentist should always choose the least restrictive but safe and effective method. A thorough evaluation of the patient’s medical history and dental needs is essential. Any use of body stabilization has potential for patient injury; therefore, its use during treatment must be carefully monitored and reassessed at regular intervals. Protective stabilization around extremities or the chest must not actively restrict circulation or respiration and must be terminated if the procedure is causing severe stress to the patient. Contraindications for protective stabilization include those who cannot be immobilized safely due to associated physical or medical conditions. For example, the use of protective body stabilization may compromise respiratory function for the patient who has a respiratory dysfunction such as asthma.

Informed consent from the patient or legal caregiver must be obtained before treatment. An explanation regarding the need for stabilization, proposed methods, risks and benefits, and possible complications is necessary.

Any discussion should allow an opportunity for the patient or caregiver to respond. Documentation in the record must include:

• Informed consent

• Indication for use

• Type of protective stabilization

• Duration of application

• Behavior evaluation during procedure

• The level of success or failure of the procedure23,25

ACCESS TO CARE

It is ideal to believe that everyone in this country should have regular oral healthcare; however, the reality is very different, especially for the disabled. There are several reasons why this is the case. Most practitioners and office staff feel uncomfortable treating patients with special needs due to lack of adequate training in school. To eliminate this disparity the American Dental Association’s Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) in 2004 adopted new standards for education programs to ensure didactic and clinical opportunities to better prepare dental professionals for the challenge.3 Cost is a considerable barrier to care. The disabled patient will typically rely on Medicaid for dental services. Inadequate compensation, extra time for treatment, extensive paperwork, and appointment no-shows are a few reasons why practitioners hesitate to participate in Medicaid. Budget deficits in federal, state, and local government support limit needed dental services for adults.11 There are practitioners who feel that if individuals with special needs are treated in their offices then the office will be inundated with referrals from other practices.

The Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination against a person with a disability who is seeking access to dental services. Title 3 of the law requires dentists to serve persons with disabilities. While patients with severe disability may require treatment in a hospital, “the majority of persons with physical or mental disabilities can be treated in the dental office environment with little if any modification in routine protocol.”7

SUMMARY

As dental professionals we must consider that there is a large number of individuals with special needs living in our communities requiring oral healthcare. The latest research linking systemic issues to the oral environment makes providing treatment crucial for patients with disabilities. Mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act, it is the profession’s duty by law to provide access to care.7 Lastly, the ethics of the dental profession obligate the dental team to provide treatment to those in need. Persons with disabilities do present challenges for the dental team but most can receive care in the private office with a few modifications to treatment. The first step that will allow access to care for these patients starts with the physical space of the practice. Most new buildings are designed to code and are considered “barrier-free.” For an existing office space, some simple changes will enable compliance with the ADA while providing access to care for everyone.

Pretreatment planning, proper patient assessment, scheduling, and possible desensitization techniques help make a successful appointment possible. Because of sudden involuntary movements or behavior issues, the patient may require some form of protective body stabilization. Thorough medical history, informed consent before treatment, and proper documentation are essential. Patients who use a wheelchair present a different set of challenges.

According to Bird and Robinson in the text Torres and Ehrlich Modern Dental Assisting, the dental assistant has three important roles in the provision of oral healthcare for patients with special needs:

1. Knowledge of specialized techniques and equipment is critical to speed and ease treatment.

2. Preventive dentistry is important for all patients but particularly for those with physical, medical, or mental challenges. The assistant may be asked to work with the patient, family, or caregiver in developing and implementing a preventive program tailored to the needs of that patient.

3. Reducing anxiety for those who have had painful medical experiences by creating a comfortable relaxed atmosphere will provide a stress-free environment for everyone involved in the dental visit.13

It is essential that the dental team be ready to treat the special needs patient. As the American population continues to live longer the dental team must be prepared to treat all patients safely and with respect.

REFERENCES

1. PM Sfikas. What’s a “disability” under the Americans with Disabilities Act? J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127;1406-1408.

2. Eshenaur A Spolarich. Persons with disabilities. In: Darby and Walsh. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2003: 764-781.

3. HB Waldman, SJ Fenton, SP Perlman, DA Cinotti. Preparing dental graduates to provide care to individuals with special needs. J Dent Ed. 2005;69(2):249-254.

4. HB Waldman. Evolving realities of dental practice: care for patients with special needs. The Dental Assistant. 2005;74(5):24-27.

5. L Lawton. Providing dental care for special patients, tips for the general dentist. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1666-1670.

6. S Perlman, S Fenton, C Friedman. Something to smile about. In: Oral Healthcare for People with Special Needs: Guidelines for Comprehensive Care. River Edge, NJ: Exceptional Parent, Psy-Ed Corp. 2003: 3-4.

7. D Tesini, SJ Fenton. Oral health needs of persons with physical or mental disabilities. Dent Clin N Am. 1994;38(3):483-498.

8. SJ Fenton, H Hood, M Holder, et al. The American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry: eliminating health disparities for individuals with mental retardation and other developmental disabilities. J Dent Ed. 2003;67(12):1337-1344.

9. S Perlman, S Fenton, C Friedman. Forewarned is forearmed. In: Oral Healthcare for People with Special Needs: Guidelines for Comprehensive Care. River Edge, NJ: Exceptional Parent, Psy-Ed Corp. 2003: 6-7.

10. Oral Conditions in Children with Special Needs. A Guide for Healthcare Providers 2001. Available from: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. National Oral Health Information Clearinghouse. 1 NOHIC Way, Bethesda, MD 20892–3500. Available at www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov.

11. HB Waldman, SP Perlman. Special care dentistry specialty: sounds good, but... J Dent Ed. 2006;70(10):1019-1022.

12. P Farsai, J Calabrese. Dental treatment for adults: oral health for adults with disabilities. In: Oral Healthcare for People with Special Needs: Guidelines for Comprehensive Care. River Edge, NJ: Exceptional Parent, Psy-Ed Corp. 2003: 36-38.

13. DL Bird, DS Robinson. The medically and physically compromised patient. In: Torres and Ehrlich Modern Dental Assisting. 9th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2004:426.

14. EM Wilkins. Care of patients with disabilities. In: Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009: 870-898.

15. DJ Stiefel. Dental care considerations for disabled adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2002;22(3):26S-39S.

16. A Dougal. J Fiske. Access to special care dentistry, part 1. Access. Br Dent J. 2008;204:605-616.

17. HB Waldman. Evolving realities of dental practice: care for patients with special needs. The Dental Assistant. 2005;74(5):24-27.

18. RL Mace. Removing Barriers to Health Care. A Guide for Health Professionals. Produced by The Center for Universal Design and The North Carolina Office on Disability and Health. Available at: http://www.fpg.unc.edu/~ncodh/rbar/. Accessed June 19, 2008.

19. US Department of Justice. Americans with Disabilities Act. ADA Home Page. Information and Technical Assistance in the Americans with Disabilities Act. Available at: http://www.ada.gov. Accessed October 26, 2008.

20. Academy of General Dentistry. The Big Picture. Special needs patients. Dental Abstracts. 2008; May-June; 53(3):121-22. Available at http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0011848608000654. Accessed October 10, 2008. (original article: Horbelt CV. Caring for the person with special needs: A rewarding professional responsibility. Gen Dent. 2007: pp. 502-505).

21. SJ Fenton. CV Horbelt. The ABC’s for successful dental treatment. In: Oral Healthcare for People with Special Needs: Guidelines for Comprehensive 10 Care. River Edge, NJ: Exceptional Parent, Psy-Ed Corp. 2003: 18-20.

22. Southern Association of Institutional Dentists. Managing Maladaptive Behaviors. The Use of Dental Restraints and Positioning Devices. Self-Study Course (a series of 15 Modules) Available at: http://saiddent.org/modules.asp. Accessed October 10, 2008.

23. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Available at: http://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/g_behavguide.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2008.

24. DECOD Program (Dental Education in Care of the Disabled). Module XII. Oral health care for persons with disabilities. (A series of 12 booklets). 2nd ed. Seattle: DECOD, School of Dentistry, University of Washington; 1998.

25. C Connick, Friedman. The role of protective support: Appropriate use of restraint in the dental treatment of people with special needs. In: Oral Healthcare for People with Special Needs: Guidelines for Comprehensive Care. River Edge, NJ: Exceptional Parent, Psy-Ed Corp. 2003: 21-23.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

At the time of original publication, Janet Jaccarino, CDA, RDH, MA, is an assistant professor in the Department of Allied Dental Education in the School of Health Related Professions at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. She has been teaching dental hygiene and dental assisting students since 2000.

www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov

www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov

www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov

www.nohic.nidcr.nih.gov