You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

GLOSSARY

Acidogenic - acid producing

Antimicrobial - destroying or suppressing the growth of microorganisms

Buffer - a substance that minimizes a change in pH of a solution by neutralizing added acids and bases

Calculus - hard mineralized deposit on the teeth

Carbohydrates - a group of chemical compounds, including sugars, starches, and cellulose

Carcinogenic - a cancer causing agent

Cariogenic - a caries causing agent

Cavitation - pitting of the enamel, resulting in caries

Chronic - of long duration

Circumscribed - to confine within boundaries

Demineralize - a process by which mineral components are removed from mineralized tissues

Dentifrice - toothpaste, or tooth cleaning compound

Diastema - abnormally large space between teeth

Enamel - the outer surface of the crown of the tooth

Erythroplakia - a flat red patch or lesion in the mouth

Erythematous - a redness of the tissue, often a sign of inflammation or infection

Etiology - the study of the cause of a disease

Expectorate - to spit

Hyperplastic - unusual growth in a part of the body, caused by excessive multiplication of cells

Hypersalivation - excessive production of saliva

Incipient - early beginning or development of a cavity

Infectivity - capable of producing infection

Interproximal - the area between two adjacent teeth

Localized - confined to a specific area

Malignant - a disease or condition likely to cause serious harm or death

Metastasis - transmitting from one area of the body to another

Neoplasm - abnormal growth of tissue; tumor

Papilla - gingiva in the interproximal spaces

Papillomavirus - viruses that cause benign epithelial tumors

Paresthesia - abnormal or impaired skin sensation

Pathology - study of the nature of a disease; abnormal manifestations of a disease

Periodontal - tissues surrounding the teeth

Plaque - a soft deposit on the teeth

Polysaccharides - a group of nine or more monosaccharides joined together

Premalignant - precancerous

Prognosis - a prediction of the outcome of a disease

Remineralization - a process enhanced by the presence of fluoride whereby partially decalcified tooth surfaces become recalcified by mineral replacement

Subgingival - below the gingiva

Sucrose - a type of sugar

Sulcus - groove or depression

Systemic - affecting the entire body

Supragingival - above the gingiva

Ulcerated - to form an ulcer

Ventral - lower surface of the tongue

Xerostomia - a lack of saliva causing unusual dryness of the mouth

Prior to the 1960s, dentistry entailed mostly emergency appointments and extraction of teeth. Today, dentistry in the United States includes many different preventive practices, such as prophylaxis, fluoride treatments, full-mouth and bite-wing radiographs, sealants, and other forms of primary preventive treatments used to prevent dental caries and periodontal disease.

CARIES RISK ASSESSMENT

Dental caries is defined as a transmissible localized infection caused by a multi-factorial etiology. In order for dental caries to develop, four interrelated factors must occur: (1) the patient’s (host) diet must consist of repeated digestion of refined carbohydrates; (2) the host’s resistance to disease is decreased; (3) the factor of time; and (4) there must be a specific bacteria (Streptococci mutans or S. mutans) present in the dental plaque.

The S. mutans play an active role in the early stages of the caries process, whereas the bacteria lactobacilli contribute to the progression of the carious lesion. Without bacteria, no caries can develop. Carious lesions must be diagnosed in conjunction with both a clinical examination and imaging to verify suspicious lesions — especially interproximal lesions. Light fluorescence may also be used as an adjunct in caries diagnoses.

Enamel is the most highly mineralized hard tissue in the body. The enamel matrix is made up of a protein network consisting of microscopic mineralized hydroxyapatite crystals arranged in rods or prisms. The protein network facilitates the diffusion of fluids, such as calcium and phosphate ions distributing these ions throughout the enamel. As carbohydrates are consumed by the host, the carbohydrates are broken down in the oral cavity by the protein enzyme amylase. This reaction causes lactic acid to be produced, thereby demineralizing the enamel matrix. If the demineralization of enamel is not reversed by the action of fluoride or, calcium and phosphate ions, then the demineralization process continues further into the tooth structure, affecting the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ) and eventually the dentinal layer. The term “overt or frank” caries is used when it reaches the DEJ.

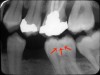

A carious lesion develops in three stages of demineralization. The first stage in demineralization of enamel is called the incipient lesion or “white spot” (Figure 1). This beginning carious lesion can be reversed with the daily use of fluoride or calcium and phosphate, persistent oral hygiene care, and a reduction of refined carbohydrates. The second stage involves the progression of demineralization leading to the DEJ and into the dentinal layer. The third stage is the actual cavitation in the dentinal layer. Neither of the last two stages can be reversed and require mechanical removal of dental caries.

There are three levels of preventive dentistry that the dental professional should understand when educating patients in the dental caries process. The first step is primary prevention. This prevents the transmission of S. mutans and delays the establishment of bacteria in infants, toddlers, and young children. The second step is secondary prevention, which prevents, arrests, or reverses the microbial shift before any clinical signs of the disease occur. The third step focuses on limiting or stopping the progression of the caries process by initiating remineralization therapy of existing lesions.

Prevention Step One - Transmission and Establishment of S. Mutans

Specifically, bacteria are transmissible via the parents or other primary caregivers. The most common routes of infection are from close contact with the child and from everyday nursing items, such as baby bottles, pacifiers, and spoons. The colonization of S. mutans is facilitated by a frequent sucrose-rich diet of the parent/caregiver, as well as the child. The higher the count of S. mutans present in the primary caregiver’s oral cavity, the more risk for the child. Another important factor in the caries process is that the earlier the S. mutans are introduced into the oral cavity and the greater number of bacteria present, the more likely it is that caries will develop in both the primary and permanent dentition. The “window of infectivity” of S. mutans is usually between ages 19 months and 31 months. For these reasons education of the parents and primary caregivers is extremely important.

Prevention Step Two - Microbial Shift

Once S. mutans and lactobacilli bacteria are established in the oral cavity, the greater the risk for future caries to develop. Where biofilm (plaque) accumulates, the bacterial count is considered to be higher, as in areas in the oral cavity that are difficult to reach during oral hygiene, such as pit and fissures. Newly erupted teeth are deficient in mineral content (calcium and phosphate), making them more susceptible to bacteria. By introducing antimicrobial agents, such as fluoride the bacterial count may be significantly reduced.

Prevention Step Three - Demineralization of Enamel

When refined carbohydrates are introduced into the oral cavity, lactic acid production occurs as an end product of S. mutans, causing the saliva pH to drop from a neutral pH of approximately 7 to an acidic pH of 4.5-5.0. This metabolizing acidogenic bacteria’s lactic acid production begin to demineralize the enamel. Common reasons for the prolonged acid conditions include: increased carbohydrate intake, reduced clearance of lactic acid due to low saliva content (hyposalivation or xerostomia), impaired saliva pH buffer capacity, and biofilm accumulation due to insufficient oral hygiene care. The more acidogenic bacteria present, the more lactic acid produced.

When saliva is released into the oral cavity via the salivary glands, the pH of the saliva returns to normal or an approximate pH of 7 and a period of remineralization (repair) occurs. This process is facilitated if fluoride or calcium and phosphate ions are present locally. The balance between demineralization and remineralization is crucial. If the balance is not maintained and demineralization occurs too frequently, then an incipient lesion will occur. This incipient or ‘white spot’ lesion may take up to approximately 9 months or more to be seen via digital imaging or radiographically as a radiolucency or dark spot on a bite-wing radiograph.

Carious Lesions Occur in Four General Areas of the Tooth

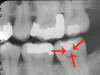

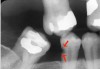

Pit and Fissure Caries (Figure 2). Includes Class I occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth, lingual pits of maxillary incisors, buccal surfaces of mandibular molars.

Smooth Surface Caries and Interproximal Surface Caries (Figure 3). Includes Class V buccal, lingual surfaces of anterior and posterior teeth and Class II interproximal surfaces of all teeth below the interproximal contact points.

Root Surface Caries (Figure 4). A more common lesion now found clinically, due to patients keeping their teeth longer.

Secondary or Recurrent Caries (Figure 5). Includes caries seen adjacent to or beneath an existing restoration.

By definition, caries risk assessment is to predict future caries development before the clinical onset of the disease. Risk factors are the lifestyle and biochemical determinants that contribute to the development and progression of the disease. Examples of patients who are at risk include those with certain socioeconomic factors (low education level, social deprivation, low income), those with certain factors related to general health (diseases, a physically or mentally compromised individual), and those with epidemiologic factors (living in a high-caries family or having a high past-caries experience). The key to dental caries risk assessment is to determine the possible risk factors and establish an individual treatment plan for each patient.

Methods to Determine Caries Risk

Oral Risk Factors: new carious lesions?; progression of previous carious lesions?; recurrent caries around restorations?

Oral Hygiene: plaque present?; calculus present?; bleeding on probing >20%?; motivation?

Dietary Analysis: carbohydrate intake?; including frequency and texture (sucrose/fructose drinks, sticky foods)?

Microbial and Salivary Factors: bacterial count?; xerostomia?; physiological conditions?; prescription drugs affecting saliva rate?; salivary stones?

Family or Social Risk Factors: >5 in-between carbohydrate meals/day ingested?; dental fear?; cooperation problem?; parent’s caries history?

Medical Risk Factors: chronic diseases?; medically or physically challenged?

Each of these categories must be addressed at each dental examination to determine risk assessment, as a patient’s oral condition may be different due to physiological changes or self-care practices. A current report should be placed in the patient’s chart. Oral instructions at their appointment, as well as written instructions are given to the patient before they leave indicating their home or self-care instructions.

SKIN, LIP, AND ORAL CANCER

The patient must be screened for oral cancer at the initial appointment and each routine dental examination by performing an extraoral and intraoral examination. Imaging is normally prescribed based on an individual’s diagnoses, but suspicious areas in the oral cavity may require additional imaging. There are various types of pathology lesions found in the oral cavity and the head and neck regions. Even though the allied dental professional cannot diagnose lesions, they should be educated in oral pathology to “interpret” lesions when assisting the dentist in his or her diagnosis. Four categories are explained in this course. Each dental facility should have oral pathology books and/or online resources with color photographs available for the dental professionals to assist with diagnoses.

Four Types of Pathologies

Candidial Leukoplakia (Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis) – “White Lesion” (Figure 6)

Etiology — an infection of the oral mucosa caused by fungus; candida albicans or infected epithelial tissue, which becomes hyperplastic with a formation of excess surface keratin (callused).

Typical Visual Cues — a circumscribed white plaque found at the site of fungal infection that will not rub off with gauze, most often found on the anterior buccal mucosa adjacent to the commissure (corner of the mouth); may occasionally be found at the lateral border of the tongue.

Useful Clinical Information — more common in adults, considered a painless and persistent lesion.

Treatment Recommendations — antifungal agents for treatment of oral candidiasis, such as Mycostatin Nystatin, Mycelex clotrimazole, or Fungizone amphotericin B. Systemic antifungal agents for chronic candidiasis include: Nizoral Ketoconazole, Diflucan Fluconazole or Sporanox Itraconazole.

Clinical Significance — oral lesions found in tobacco users should be viewed with increased suspicion for possible pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions.

Erythroplakia – “Red Lesion” (Figure 7)

Etiology — a significant risk factor to the oral mucosa is chronic exposure to carcinogenic components found in all types of tobacco. The other common risk factor is chronic alcohol exposure. Even worse is a combination of both.

Typical Visual Cues — a circumscribed, or ill-defined, erythematous plaque that varies in size, thickness and surface configuration. It has a velvety appearance and occurs most frequently on the floor of the oral cavity, ventral area of the tongue and the soft palate.

Useful Clinical Information — a painless and persistent lesion, found more commonly in adult males and patients who report tobacco exposure.

Treatment Recommendations — the patient should be counseled in a tobacco cessation program if biopsies reveal that the lesion is premalignant. Then, a more extensive therapy is indicated and the patient should be re-evaluated at regular intervals for other oral mucosal changes.

Clinical Significance — erythroplakia occurs less frequently than leukoplakia, but it is much more likely to exhibit microscopic evidence of premaligancy.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Figure 8)

Etiology — idiopathic (unknown). Risk factors include: tobacco use, alcohol use, sun radiation, genetic predisposition, nutritional deficiency, immunosuppression, and infections, such as candidal leukoplakia and human papillomavirus.

Typical Visual Cues — a deep-seated ulcerated mass, fungating ulcerated mass, ulcer margins commonly elevated, adjacent tissues commonly firm to palpation, and may have residual leukoplakia and/or erythroplakia.

Useful Clinical Information — more common in adult males, continuous enlargement, local pain, referred pain often to the ear, and paresthesia often of the lower lip.

Treatment Recommendations — patient should be counseled to stop tobacco use and given a referral to a local medical treatment facility for appropriate treatment (surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy), and a careful periodic re-evaluation.

Clinical Significance — early diagnosis is essential for cure, presence of lymph node metastasis greatly worsens the prognosis, approximately 50% of patients have evidence of lymph node metastasis at time of diagnosis (that is why the extraoral examination is so critical at the time of each intraoral examination), and patients who have had one cancer are at greater risk of having a second oral cancer. The overall 5-year survival rate is 45%-50%.

Etiology — a malignant neoplasm of melanin-producing cells. Chronic exposure to sun radiation and a fair complexion increases the risk for skin lesions.

Typical Visual Cues — larger than 0.5 cm in diameter, irregular margins, irregular pigmentation, any change in pigmentation, ulceration of the overlying mucosa, macular (superficial spreading) or elevated (nodular), and most often occurs on gingiva and the palate.

Useful Clinical Information — occurs most often in adult males, usually painless, rapidly enlarging.

Treatment Recommendations — refer to a local medical treatment facility for the appropriate surgery and chemotherapy.

Clinical Significance — malignant melanoma is an extremely aggressive form of cancer, early diagnosis is essential for cure, patients with oral mucosal lesions generally have a poor prognosis. For skin, the 5-year survival rate is 65%and for oral the rate is 20%.

Oral Management for the Cancer Patient

Bacterial Plaque Control: Start oral hygiene instruction at first appointment and emphasize preventive infection control procedures and potential oral side effects associated with cancer therapy. Toothbrushing instructions include using a soft or extrasoft toothbrush; a flavored dentifrice may not be tolerated, but fluoride is essential. Mouthrinses include saline solution to moisten the mucosa or baking soda rinses for managing oral mucositis. Chlorhexidine gluconate rinsing may also be recommended for antibacterial properties. Commercial mouthrinses that contain alcohol should be avoided.

Daily Fluoride Therapy: Daily fluoride therapy is indicated for patients about to undergo head and neck radiation therapy, if the salivary glands are in the field of radiation. Make impressions and fabricate a custom fluoride tray, advise the patient to apply custom trays lined with prescription neutral sodium fluoride gel to the teeth for four minutes once daily or use brush-on sodium fluoride varnish. Advise patient to refrain from eating, drinking, or rinsing for 30 minutes following fluoride application.

Dietary Instructions: Instruct the patient in the preparation of foods. Avoid highly cariogenic foods such as carbohydrates and also spicy foods. A soft, bland diet is recommended. Water is recommended throughout the day to moisten the oral cavity. Saliva substitutes are also recommended to decrease the risk of caries.

Avoid Alcohol and Tobacco Products: If the patient uses tobacco products, a logical step for the cancer patient is to start tobacco cessation counseling. See the ADAA continuing education course on tobacco cessation for further recommendations.

ORAL HYGIENE EDUCATION

The Development of Dental Plaque

Plaque is a biofilm that contributes to two oral diseases: dental caries and periodontal disease. It is a complex community of microorganisms that have a negative surface charge that attaches to the host surface enamel or gingiva. Biofilm can also contribute to peri-implantitis. The initial layer or formation of plaque is called the acquired pellicle. This layer will reform within two hours after removal and will also form on artificial prosthesis, such as dentures. With over 700 species of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in the human oral cavity, microbes grow as complex colonies in biofilm. In fact, it takes only two days for plaque to double in mass. Plaque requires the following to metabolize: streptococci mutans and a processed carbohydrate. The end product, lactic acid consists of intracellular polysaccharides and extracellular polysaccharides. When plaque is not removed from the oral cavity it may mineralize and become calculus. This mineralized formation is formed by calcium and phosphates in the saliva and it has been found that tobacco use accelerates the formation of calculus. However, recent research studies link plaque as the contributing factor to periodontal disease rather than calculus. Daily removal of biofilm is critical to reduce oral diseases.

Manual Versus Powered Toothbrushes

Both manual and power toothbrushes can effectively remove plaque if patients use correct technique and brush for an adequate time period. Certain toothbrush designs, however, provide more effective removal than others. Some studies show oscillating-rotating power brushes can be more effective at plaque removal than manual brushes. Power toothbrushes were shown to be as safe to use as manual toothbrushes if used properly.

There are several manual toothbrushing techniques. They include the horizontal scrub, Bass, Stillman, Charters, and Fones, to name a few. The most popular method that an uneducated patient uses is the horizontal scrub. Unfortunately, gingival and enamel damage can occur with aggressive strokes and too firm of bristles. The Stillman method is used for massage and stimulation of the gingiva with a 45 degree angle of the bristles and a vibratory/pulsing method. The Charter method also involves a 45 degree angle with the bristles and a rotary or vibratory motion forcing the bristles interproximally. The Charter’s method can be recommended for orthodontic patients to clean ortho brackets and bands.

A preferred method for adults is the Modified Bass Method (Figure 10). This method was the first to focus on the removal of plaque and debris from the gingival sulcus with the combined use of the soft toothbrush and dental floss. The method is effective for removing plaque at the gingival margins and controlling plaque that leads to periodontal disease and caries. In the Bass technique, the toothbrush is positioned in the gingival sulcus at a 45-degree angle to the tooth apices. A vibratory action, described as a back-and-forth horizontal jiggle, causes a pulsing of the bristles to clean the sulcus. The term ‘modified’ indicates a final “sweep” with the toothbrush toward the occlusal surfaces to remove debris subgingivally. Ten strokes are recommended for each area. This is the only toothbrush method that places the toothbrush bristles into the sulcus.

For children, the rotary method called the Fones technique (Figure 11) is preferred since children do not have the manual dexterity for a more advanced technique. The Fones technique is a circular method similar to the motion of the old rotary telephone. The teeth are clinched and the toothbrush is placed inside the cheeks. The toothbrush is moved in a circular method over both the maxillary and mandibular teeth. In the anterior region, the teeth are placed in an edge-to-edge position and the circular motion is continued. Children adapt to this technique rather quickly.

There are many powered toothbrushes available on the market. There are also less expensive battery-powered toothbrushes available for patients to try. Studies have shown powered toothbrushes are an excellent tool for all patients, particularly those with low manual dexterity or physical limitations. The larger handle is ideal for patients who cannot grip the smaller manual toothbrush handles, such as patients with arthritis or stroke victims. The patient should be encouraged to try both manual and powered toothbrushes and determine which is best for them. However, the patient should be instructed to use the new toothbrush for at least four weeks. It takes approximately 30 days for someone to develop a habit. Trying new dental products requires time for patients to adapt to new habits.

Whichever toothbrush is used, the patient should be taught to remove plaque in a sequential order when brushing to make sure they don’t skip any surface areas of the enamel or exposed cementum. The patient should be shown in the mirror the proper technique and their instruction should also include brushing their tongue to remove debris and bacteria. The patient should show that they understand their oral hygiene instruction by demonstrating it back to the dental professional. A combination of oral and written instructions is always preferred. Studies have shown that too much instruction at one time is overwhelming for the patient and they will not adopt new habits unless they understand and believe that they have value and are important.

Auxiliary Aids

Dental Floss and Flossing Methods: There are many different types of floss or tape on the market: waxed vs. unwaxed, mint vs. cinnamon or bubblegum, floss vs. floss holders or floss threaders. Many patients will ask: “Is waxed floss or unwaxed floss better?” The answer should be simply, “I’m glad you’re flossing. It’s whatever you prefer.” Some studies indicate that waxed floss is preferred because it gets through the contact points easier. Other studies indicate that dental professionals are concerned with the amount of wax that may accumulate in the gingival sulcus.

Another question patients ask frequently is, “Do I floss before or after brushing?” Again, it doesn’t matter. As long as they are flossing properly, dental professionals are thrilled. The point of brushing and flossing is plaque removal. By removing the irritant plaque and reducing the bacterial count in the saliva, the patient is making a significant difference in preventing caries and periodontal disease.

There are two flossing methods available to teach your patients. One is the circle or loop method and the other is the spool method. The circle or loop method is preferred for children or any patient with low manual dexterity. A piece of floss approximately 18-24 inches long is tied at the ends to form a loop or circle. The patient uses the thumb and index finger of each hand in various combinations to guide the floss interproximally through the contacts. When inserting floss, it is gently eased between the teeth with a seesaw motion at the contact point, making sure not to snap the floss and cause trauma to the gingival papilla. Once through the contact area, gently slide the floss up and down the mesial and distal marginal ridges in a C-shape around the tooth directing the floss subgingivally to remove the debris.

The spool method (Figure 12 through Figure 14) utilizes a piece of floss approximately 18-24 inches long where the majority of the floss is loosely wound around the middle finger of one hand and a small amount of floss around the middle finger of the opposite hand. The same procedure is followed as the loop method when positioning the floss interproximally. After each marginal ridge is cleaned, the used floss is moved or spooled to the other hand until all supragingival and subgingival areas have been cleaned, including the distal areas of the posterior teeth.

Patients with fixed prosthesis such as bridges, orthodontics, and bonded orthodontic retainers should be encouraged to use floss threaders (Figure 15 and Figure 16) to remove debris. The floss is threaded underneath the prosthetic to remove any debris caught underneath. Patients should be instructed on their use and again asked to demonstrate to the dental professional that they understand and know how to use it.

Floss holders are an alternative if the patient has difficulty flossing manually or for a patient with large hands, physical limitations, a strong gag reflex, or low motivation for traditional flossing. A floss holder is a good alternative to not flossing at all and should be shown to patients as a means of removing plaque.

Toothpicks or Wooden/Plastic Triangular Sticks: If your patients have large diastemas or food impaction areas, they should be encouraged to utilize interproximal sticks (Figure 17) such as Stim-U-Dents®. Made of balsa wood, Stim-U-Dents® are used to remove debris and plaque, and are preferred by dental professionals over standard toothpicks because toothpicks can splinter into the gingiva and damage the gingival tissue. If patients do not have access to floss, they can use the wooden balsa sticks to remove plaque and stimulate the gingiva.

Interproximal and Uni-tufted Brushes: These small interproximal brushes are attached to handles and are used for large spaced interproximal areas and for orthodontic patients to use between their brackets to remove debris. There are a variety of brushes available, including travel sizes for pockets and purses. The brushes are tapered for easy access to difficult areas and patients seem to adapt well to instructional use.

FLUORIDES

Both community water fluoridation, known as systemic or pre-eruptive fluoride and topical fluoridation also known as post-eruptive fluoride have proven to be an important mechanism in preventing dental caries in the United States since the 1950s. Through studies, researchers have discovered that not only has water fluoridation contributed to the decline in dental caries, but also the post-eruptive effect of fluoride has played an even more vital role in reducing dental caries.

Current Theories Regarding Fluoride Use

The current theory is that a daily use of fluoride-containing dentifrices has significantly reduced the dental caries level in the United States. Other sources of fluoride include: added fluoride to city water sources; naturally occurring water fluoride in well water; fluoridated dentifrices (toothpastes); over-the-counter mouthrinses; processed food and beverages at manufacturing plants that utilize fluoridated city water; prescription rinses, gels, pastes, and tablets; professional fluoride varnish applications; and both in-office and at-home topical fluorides. This consistent application of fluoride to enamel has reduced dental caries and has significantly changed how dentistry is practiced today.

By current convention, many dental professionals administer professional topical fluoride treatments to patients at their preventive maintenance appointments. However, is this routine procedure necessary for every patient? Although concentrated topical fluoride treatments usually are intended for annual or semiannual prophylaxis visits, a decline in caries prevalence brings into question the continuing need for such treatment in individuals who are caries-free, at a low caries risk, use a fluoridated toothpaste, and ingest fluoridated water. The decision to use a professionally applied topical fluoride should be based on a recent clinical examination, as well as scientific evidence.

Since current practice is to deliver a topical fluoride system to every young patient, the dental profession is faced with an ethical quandary when dealing with this issue. If a patient does not show evidence of active caries, should the patient be given a professional fluoride treatment at the prophylaxis appointment? With exposure to so many outside sources, the patient may be receiving adequate amounts of fluoride to maintain a caries-free condition without routinely scheduled professional fluoride applications. These frequent exposures to low concentrations of fluoride, as received from toothpastes, are more effective in the prevention of caries than infrequent exposures to high concentrations of fluoride, as received from professional treatments. The American Dental Association (ADA) utilizes evidence-based research when making clinical recommendations. The ADA states that “patients whose caries risk is lower may not receive additional benefit from professional topical fluoride.” Recommendations to use topical fluoride applications on your patient should be determined by whether or not the patient is exposed to multiple sources of fluoride or has other caries risk factors.

Pre-eruptive Vs. Post-eruptive Fluoride

At the time of tooth eruption, enamel is not quite completely mineralized and will undergo what is now called the post-eruptive period (formally known as the topical effect) that will take approximately two years. Throughout this enamel maturation period, fluoride continues to accumulate in the outer surfaces of the enamel. This fluoride is derived from the saliva, as well as exposure to fluoride-containing products such as food and beverages. Most of the fluoride incorporated into the developing enamel occurs during what is now called the pre-eruptive (formally known as the systemic effect) period of enamel formation, but also occurs topically during the post-eruptive period of enamel maturation.

Types of Professional Fluoride

The three types of fluoride available for the dental professional to use to prevent or reduce caries are: 2% or 5% neutral sodium fluoride (NaF), stannous fluoride (SnF2) and 1.23% acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF). Sodium fluoride, which is available in powder, gel, foam and varnish, forms calcium fluoride in enamel after use. Sodium fluoride’s main benefit is not etching porcelain and ceramic restorations. Stannous fluoride is available in powder form in bulk and pre-measured capsules. Its use results in the formation of calcium fluoride and stannous fluorophosphate in enamel. Due to several disadvantages, including a bitter, metallic taste and a difficult preparation of use, stannous fluoride is typically not used for caries alone, but it does provide anti-gingivitis and anti-sensitivity benefits.

For many decades, an operator-applied professional fluoride method by disposable mouth tray was used with a 1.23% APF gel or foam, or a 2% sodium fluoride. This procedure offered a method that was convenient to use and was some what tolerated by patients. Topical fluoride can also be applied by “brushing it” on the teeth, especially with small children. However, tray use seemed to be the most effective and practical method for child and adult use. In the last several years, fluoride varnish has become the topical fluoride of choice by both public health professionals and now private dental practices.

One Minute vs. Four Minute Fluoride Applications

Research studies continue to show that fluoride uptake in enamel is time-dependent due to a diffusion-controlled process and that it should be left on the teeth for the full 4 minutes. Although the most update of fluoride is in the first minute, research shows that the full 4 minutes provides the best topical benefit. The ADA states “there are considerable data on caries reduction for professionally applied topical fluoride gel treatments of 4 minutes or more. In contrast, there is laboratory, but no clinical equivalency data on the effectiveness of 1-minute fluoride gel applications.”

Upon examining current information on this topic, dental professionals need to determine if professional topical fluoride applications are appropriate for all their patients, based on caries risk factors.

Individual Patient Treatment Options

The ADA recommends that for patients with active and rampant caries topical fluoride applications should be done more frequently—on a quarterly basis—regardless of whether the patient ingests optimally fluoridated water. Note that a professional prophylaxis is not needed prior to the application of professional topical fluoride products because fluoride uptake and caries inhibition are not improved by a prophylaxis. Also, the use of a fluoride prophylaxis paste does not replace a professionally applied fluoride application. Moreover, the patient with rampant caries should not only receive topical fluoride treatment on a quarterly basis, but will require a home prescriptive fluoride-treatment program as well. Patients with active caries require professionally applied fluoride applications at least twice a year. Based on a recent clinical examination, if a patient ingests sufficient fluoridated water and is caries free, then a topical fluoride treatment is not necessary. There is little fluoride deposition lasting more than 24 hours when fluoride is applied to sound, fully maturated enamel. Therefore, there appears to be no preventive benefits from the application of fluoride to adult patients with sound enamel.

Root Surface Caries on the Rise

Root surface caries has increased due to the increased retention of teeth during adulthood thanks to various caries-preventive measures and patients living longer. About one-half of US adults are affected with root surface caries by age 50, with an average of about three lesions by age 70. Fluoride is very effective in preventing root surface caries. Results of studies have demonstrated that the presence of fluoridated drinking water throughout the lifetime of an individual prevents the development of root surface caries. Furthermore, it has been observed that the use of sodium fluoride (NaF) dentifrice results in a significant decrease in root surface caries of more than 65%. There has not been much data collected on professional topical applications affecting root surface caries. But in a preclinical model, all three approved topical fluorides decreased the formation of root caries by 63% to 76%.

Fluoride Application

No matter which fluoride is utilized, when applying a fluoride via tray form, the dental professional should be aware of the following: use a small amount of fluoride in the bottom of the tray; position the patient in an upright position; use efficient saliva aspiration; request the patient expectorate thoroughly on completion of the fluoride application; ask the patient to not eat, drink or smoke for approximately 30 minutes. This procedure reduces the amount of inadvertent swallowing to less than 2 mg of fluoride, which has shown to be of little consequence.

Fluoride Varnishes

Although fluoride varnish has been used in Europe and Canada for many years, fluoride-containing varnishes have only become popular in the United States as an anti-caries agent and not just as a desensitizing agent. Recently, the benefit of fluoride varnish has become more apparent to dental professionals. Fluoride varnish has been used in public health settings as a much-needed concentrated-treatment of fluoride for children with high-caries rates. Dental professionals in private practices have started using it for their very young patients, as appropriate. In 2004 the ADA Resolution 37H stated “the ADA supports the use of fluoride varnishes as safe and efficacious within a caries prevention program that includes caries diagnosis, risk assessment, and regular dental care.” The resolution also encourages the FDA “to consider approving professionally applied fluoride various reducing dental caries, based on the substantial amount of available data supporting the safety and effectiveness of this indication.” Most varnishes contain 5% sodium fluoride with only 0.3 ml to 0.5 ml of the varnish being applied. Patient compliance, especially with small children appears to be better than with professional fluoride tray applications. The application includes starting with clean tooth surfaces and painting the varnish on the teeth (Figure 18), after drying the tooth surface. The varnish should be left on the tooth surface until the next day, as the fluoride continues to be released into the enamel. The patient should be instructed not to brush until the next morning. Always follow manufacturer’s recommendations. Based on caries risk, the fluoride varnish recommendations include reapplying at 4 to 6 month intervals. Fluoride varnish is an important dental therapy for high-risk patients.

Amorphous Calcium Phosphate (ACP)

ACP has anticariogenic properties to promote the remineralization of enamel and cementum, as well as balancing the pH of saliva and reducing dentinal sensitivity. Regular application of ACP with fluoride increases levels of calcium and phosphate levels in biofilm and tooth structure. In fact, an addition of 2% ACP (ie, Recaldent™) to as little as 450 ppm fluoride can significantly increase the incorporation of fluoride ions into biofilm and co-localize calcium and phosphate ions with fluoride ions at the tooth surface. An adjunct treatment of ACP and a 1,100 ppm fluoridated dentifrice (toothpaste) can decrease bacteria and increase mineralization. Patients who benefit from ACP include conditions such as orthodontic, white spots, polypharmacy, tooth whitening, oncology, hypersensitivity, high caries risk, xerostomia, and acid erosion due to sodas and other drinks.

DIET AND DENTAL CARIES

A number of studies have shown a clear relationship between fermentable carbohydrate consumption and dental caries. The amount of sugar in the diet is not as important in caries progression as the frequency and form of consumption. For example, foods such as raisins, processed starches (ie, pies, cakes, cookies), and candies that adhere to the teeth for some time will continue to slowly release sugar. The local bacteria (S. mutans) use carbohydrates and extends the decrease in the plaque pH. Similarly, any food or beverage that contains fermentable carbohydrates and is consumed over a prolonged period or with increased frequency will have the same effect.

Fruits in general tend to have low cariogenic potential, with the exception of dried fruits and certain fresh fruits. Apples, bananas, and grapes contain 10%-15% sucrose, citrus fruit 8%, and berries and pears only 2%. Although citrus fruits are high in water, stimulate saliva production, and provide an excellent source of vitamin C, they can potentially erode tooth enamel if consumed in large quantities over an extended period of time.

Non- or low-acidogenic foods include:

• raw vegetables, such as broccoli, cucumber, lettuce, carrots, peppers

• meat, fish, poultry

• beans, peas, nuts, natural peanut butter

• milk, cheeses, flavored yogurts

• corn chips, peanuts, popcorn

• fats, oils, butter, margarine

• non-sugar sweeteners, such as xylitol®, nutrasweet®, aspartame®, saccharin®, sucralose®

Soft drinks, sport drinks, and energy drinks containing sugar are big business in the United States. Frequent consumption of sugary drinks has long been known to contribute to dental caries. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), consumption of soft drinks in the United States has increased over the last 30 years with both adults and children. Soft drinks have been linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes. Teenagers and young adults consume more sugar drinks than other age groups. Males consume more soft drinks than females and low-income Americans consume more soft drinks than those with higher incomes.

A non-diet soft drink is made from carbonated water, added sugar, and flavors. Each can of soda contains the equivalent of about 10 teaspoons, or 40 grams, of sugar. Mountain Dew® is so popular in the United States that the coined phrase “Mountain Dew Mouth” is a recognized term used by the dental profession for patients diagnosed with rampant caries and/or erosion.

PIT AND FISSURE SEALANTS

Sealants have been endorsed by the American Dental Association (ADA) and the United States Public Health Service as being effective in preventing pit and fissure caries. Pit and fissure caries accounts for over 80% of active caries in children; however, these surfaces make up only 15% of the total tooth surfaces. Sealants must not be overlooked as another form of preventive dentistry, along with plaque control, fluoride therapy and sugar discipline.

The disease susceptibility of the tooth should be considered when selecting teeth for sealants, not the age of the patient. Sealants appear to be equally retained on occlusal surfaces of both primary and permanent dentition. Sealants should be placed on the teeth of adult patients if there is evidence of existing or impending caries susceptibility, such as a diet excessive in carbohydrates or as a result of a drug or radiation-induced xerostomia.

Types of Sealant Materials

There are two types of resin-based sealants available today, filled and unfilled. Filled sealants are a combination of resins, chemicals and fillers. The purpose of the filler is to increase bonding strength and resistance to abrasion and wear. Due to the hardness and wear resistance of filled sealants, they must be checked after placement with articulating paper and adjusted with a dental handpiece and appropriate bur. Unfilled sealants have a higher ratio of resin to filler material, and do not need to be adjusted with a dental handpiece; they are in essence self-occluding. Due to high viscosity (rate of flow) of unfilled sealants, they readily flow into the pits and fissures.

Because fluoride uptake increases the enamel’s resistance to caries, the use of a fluoridated resin-based sealant may provide an additional anticariogenic effect. Fluoride-releasing sealants have shown antibacterial properties, as well as a greater artificial caries resistance compared to a non-fluoridated sealant material. The fluoride will leach out over a period of time into the adjacent enamel. Eventually the fluoride content of the sealant should be exhausted, but the content of the enamel greatly increased.

Criteria for Selecting Teeth for Sealants

The criteria for selecting teeth for sealant placement are a deep occlusal fissure, fossa (Figure 19), or incisal lingual pit. A sealant may be contraindicated if: a patient’s behavior does not permit the required dry-field to place sealants; an open carious lesion exists; caries exist on other surfaces of the same tooth and restoration will disrupt an intact sealant; a large occlusal restoration is already present.

The Four Commandments for Successful Sealant Retention

For sealant retention the surface of the tooth must: have a maximum surface area; have deep, irregular pits and fissures for better retention; be clean; and, most crucial to retention, be absolutely dry and uncontaminated with saliva residue at the time of the sealant placement.

All of these criteria must be present for a sealant to be retained. If within a few months the sealants are lost, it is most likely due to faulty technique by the clinician.

The Pit and Fissure Sealant Procedure

It is highly recommended that sealant application be performed as a two-person procedure. Even when the patient is an adult, isolation and application are difficult with just one clinician.

1) Prior to the application of a tooth conditioner, the tooth surface should be cleaned by air polishing, polishing with non-fluoridated pumice paste, hydrogen peroxide, or enameloplasty. All heavy stains, deposits, debris, and plaque should be removed. After cleaning the occlusal surface, dry the area thoroughly for 10 seconds.

2) Increasing the surface area requires tooth conditioner/etchant, composed of 30%-50% concentration of phosphoric acid. Since sealants do not directly bond to the teeth, the adhesive force must be improved by tooth conditioner. If any of the tooth surfaces do not receive the tooth conditioner, the sealant will not be retained. Application usually includes a small sponge applicator or cotton pellet held with cotton pliers. Isolation of the teeth includes cotton rolls, dry-angles, or ideally with a dental dam. Follow manufacturer recommendations for time. Rinse for 10 seconds. The appearance of the enamel by the tooth conditioner is white, dull and chalky. If the enamel does not appear white and chalky, tooth conditioner is reapplied according to manufacturer instructions. Dry thoroughly before sealant application.

3) The application of the sealant material requires the pits and fissures to be filled and the material brought to a knife-edge approximately halfway-up the inclined plane of the cusp ridge (Figure 20). Any bubbles must be broken before polymerization to prevent a defect. Polymerize with a curing light. Follow manufacturer directions for time.

4) Check the sealant with an explorer for proper placement and polymerization. Check occlusion with articulating paper and check interproximal contacts with floss. If sealant material is present interproximal, use a scaler to remove excess. If occlusion is high, use a slow-speed rotary bur such as a no. 4 round or no. 8 round bur. Recheck the occlusion again. Sealants should be checked at each annual dental examination for retention.

MOUTHGUARDS AND SPORTS DENTISTRY

Whether for exercise, competition, or the simple enjoyment of recreational activity, increasing numbers of health-conscious Americans are involved in sporting activities. Approximately 30 million children participates in various sports programs and another 80 million are involved in unsupervised recreational sports. Dentistry plays a large role in treating oral and craniofacial injuries resulting from sporting activities.

Prior to the 1980s, little was available in the scientific literature in terms of sports-related injury assessment. Several injury surveillance systems have been established in an attempt to track sports-related accidents and injuries. While all injury surveillance systems provide valuable information on generalized sports injuries, very little information is available regarding dental or craniofacial injuries. In terms of data collection and analysis of dental injuries due to sporting activities, the field continues to be open for dentistry to assume a major leadership role in assessing dental injuries resulting from sporting activities.

Statistics

More than 5 million teeth are knocked out each year; many during sports activities, resulting in nearly $500 million spent on replacing these teeth each year. In an issue of Dental Traumatology it was reported among children ages 13-17, sports-related activities were associated with the highest number of dental injuries. Males are traumatized twice as often as females, with the maxillary central incisor being the most commonly injured tooth. Studies of orofacial injuries published over the last twenty years reflects various injury rates dependent on the sample size, the age of participants, and the specific sports. In soccer, where rules are not uniform on wearing mouthguards, only a small percentage of the participants wear them. In baseball and softball, again only 7% wear mouthguards. The National Federation of State High School Association (NFHS) recently stated that of all injuries less than 1% are oral injuries because football players are wearing properly fitted mouthguards. Prior to the use of mouthguards, injuries to the orofacial areas occurred over 50% of the time. The NFHS recommends mouthguards for any sports where there is a potential for orofacial injury from body contact. It is clear that the need for studies, education, and regulations for mouthguard implementation is a major concern in the dental field.

All athletes constitute a population that is extremely susceptible to dental trauma. Dental injuries are the most common type of orofacial injury. An athlete has a 10% chance of receiving an orofacial injury every season of play. It is estimated that mouthguards prevent between 100,000 and 200,000 oral injuries per year in professional football alone. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and the American Dental Association recommend a mouthguard for all children and youth participating in any organized sports activities.

Following is a list of types of injuries an athlete may sustain that are of particular concern to the dental professional.

Soft Tissue Injuries

The face is often the most exposed part of the body in athletic competition and injuries to the soft tissues of the face are frequent. Abrasions, contusions, and lacerations are common and should be evaluated to rule out fractures or other significant underlying injury. These usually occur over a bony prominence of the facial skeleton such as the brow, cheek, and chin. Lip lacerations are also common.

Fractures

Fractures of the facial bones present an even more complex problem. One of the most frequent sites of bony injury is the zygoma (cheekbone). Fractures of the zygoma, occurring as a result of direct blunt trauma from a fall, elbow or fist, account for approximately 10% of the maxillofacial fractures seen in sports injuries. Like the zygoma, the prominent shape and projection of the mandible cause it to be frequently traumatized. Approximately 10% of maxillofacial fractures resulting from sporting activities occur in the mandible when the athlete strikes a hard surface, another player or equipment. In a mandibular fracture, airway management is the most important aspect of immediate care. In both children and adults, the condyle is the most vulnerable part of the mandible. Fractures in this region have the potential for long-term facial deformity. Recent data suggest that condylar fractures in children can alter growth of the lower face.

TMJ Injuries

Most blows to the mandible do not result in fractures, yet significant force can be transmitted to the temporomandibular disc and supporting structures that may result in permanent injury. In both mild and severe trauma, the condyle can be forced posteriorly to the extent that the retrodiscal tissue is compressed. Inflammation and edema can result, forcing the mandibular condyle forward and down in acute malocclusion. Occasionally this trauma will cause intracapsular bleeding, which could lead to ankylosis of the joint.

Tooth Intrusion

Tooth intrusion occurs when the tooth has been driven into the alveolar process due to an axially directed impact. This is the most severe form of displacement injury. Pulpal necrosis occurs in 96% of intrusive displacements and is more likely to occur in teeth with fully formed roots. Immature root development will usually mean spontaneous re-eruption. Mature root development will require repositioning and splinting or orthodontic extrusion.

Crown and Root Fractures

Crown fractures are the most common injury to the permanent dentition and may present in several different ways. The simplest form is crown infraction. This is a crazing of enamel without loss of tooth structure. It requires no treatment except adequate testing of pulpal vitality. Fractures extending into the dentin are usually very sensitive to temperature and other stimuli. The most severe crown fracture results in the pulp being fully exposed and contaminated in a closed apex tooth or a horizontal impact may result in a root fracture. The chief clinical sign of root fracture is mobility. Radiographic evaluation and examination of adjacent teeth must be performed to determine the location and severity of the fracture as well as the possibility of associated alveolar fracture. Treatment is determined by the level of injury.

Avulsion

Certainly one of the most dramatic sports-related dental injuries is the complete avulsion of a tooth. Two to sixteen percent of all injuries involving the mouth result in an avulsed tooth. A tooth that is completely displaced from the socket may be replaced with varying degrees of success depending, for the most part, on the length of time it is outside the tooth socket. If the periodontal fibers attached to the root surface have not been damaged by rough handling, an avulsed tooth may have a good chance of recovering full function. After two hours, the chance for success is greatly diminished. The fibers become necrotic and the replaced tooth will undergo resorption and ultimately be lost. See the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry website relating to avulsed teeth recommendations for dental professionals called the Decision Tree for the Management of an Avulsed Permanent Tooth.

Emergency Treatment

Due to the high incidence of sports-related dental injuries, it is vital that primary healthcare providers such as school nurses, athletic trainers, team physicians and emergency personnel are trained in the assessment and management of dental injuries. Interested dental professionals can assist these providers by offering to speak at schools or community functions, so that the primary health care providers who will deliver immediate treatment at sporting events understand the proper protocol for orofacial injuries, such as displaced teeth, avulsed teeth, lacerations and crown fractures. The ADA has urged its members to work together with schools, colleges, athletic trainers and coaches to develop mouthguard programs and guidelines to prevent sports injuries.

The main method for preventing orofacial injuries in sports is to wear mouthguards and headgear, consisting of a helmet and face protector. Parental perceptions of children’s risks to injury, expenses associated with protective gear, and peer pressure may influence use of mouthguards. The observed patterns of mouthguards wearing by males and females can represent cultural differences, peer pressure, and/or nature of sports played, including the following:

• perceptions that females are less aggressive and thus, a reduced risk of injury may exist

• perceptions regarding the absence of long-term commitment to a sport may result in a differential willingness to devote resources to females

• aesthetic appeal may influence protective orofacial gear usage; and

• females may play in non-league-based sports with fewer or less stringent rules or may play less combative sports than males

The literature indicates the behavior of athletes is most influenced by their coaches. Coaches report that most information about mouthguards comes from sales representatives, educational materials and dentists.

The Ideal Mouthguard

When considering recommendations, an ideal mouthguard: protects the teeth, soft tissue, bone structure, and temporomandibular joints; diminishes the incidence of concussions and neck injuries; exhibits protective properties that include high power absorption and power distribution throughout the expansion; provides a high degree of comfort and fit to the maxillary arch; remains securely and safely in place during action; allows speaking and does not limit breathing; is durable, resilient, tear resistant, odorless, and tasteless.

The American Society for Testing and Materials and the manufacturers of mouthguards have classified the mouthguards into three types:

Stock Mouthguards: Stock mouthguards may be purchased from a sporting goods store or pharmacy. They are made of rubber, polyvinyl chloride, or a polyvinyl acetate copolymer. The advantage is that this mouthguard is relatively inexpensive, but the disadvantages far outweigh the advantages. They are available only in limited sizes, do not fit very well, inhibit speech and breathing, and require the jaws to be closed to hold the mouthguard in place. Because the stock mouthguards do not fit well, the player may not wear the mouthguard due to discomfort and irritation. The Academy of Sports Dentistry has stated that the stock mouthguard is unacceptable as an orofacial protective device.

Mouth-Formed Protectors: There are two types of mouth-formed protectors: the shell-liner and the thermoplastic mouthguard. The shell-liner type is made of a preformed shell with a liner of plastic acrylic or silicone rubber. The lining material is placed in the player’s mouth, molds to the teeth and then is allowed to set. The preformed thermoplastic lining (also known as “boil and bite”) is immersed in boiling water for 10 to 45 seconds, transferred to cold water and than adapted to the teeth. This mouthguard seems to be the most popular of the three types and is used by more than 90% of the athletic population.

Custom-Made Mouth Protectors: This is the superior of the three types and the most expensive to the athlete. But isn’t it worth the cost to protect an athlete’s teeth from injury? Most parents will spend quite a bit of money on athletic shoes, but might not think about protecting their child’s teeth. This mouthguard is made of thermoplastic polymer and fabricated over a model of the athlete’s dentition. The mouthguard is made by the dentist and fits exactly to the athlete’s mouth. The advantages include: fit, ease of speech, comfort, and retention. By wearing a protective mouthguard, the incidence of a concussion by a blow to the jaw is significantly reduced because the condyle is separated form the base of the skull by placing the mandible in a forward position.

Dental Team’s Role

Sports dentistry should encompass much more than mouthguard fabrication and the treatment of fractured teeth. As dental professionals, we have a responsibility to educate ourselves and the community regarding the issues related to sports dentistry and specifically to the prevention of sports-related oral and maxillofacial trauma. The American Dental Association (www.ada.org) publishes brochures that explains the different types of mouthguards and their advantages. A field emergency kit is a simple and inexpensive item for the dentist attending a sporting event. Such a kit includes: gloves, mouth mirror, pen light, tongue depressor, scissors, rope wax, zinc oxide eugenol (ie, IRM), spatula, mixing pad, 2x2 and 4x4 sterile gauze, sterile small wire cutters (for removal of broken orthodontic wires), spare commercial mouthguard, and emergency tooth-preserving solution Save-a-Tooth™ for the avulsed tooth (www.save-a-tooth.com).

A dental professional’s role should include:

• good impression techniques and knowledge of mouthguard materials/manipulations in mouthguard creation.

• communications with children and parents/guardians. Dental charting should include questions about involvement in sports and the use of mouthguards. If patients are unwilling/unable to pay for an office-made guard, the dental assistant should educate patients about affordable boil and bite-type guards for minimal protection.

• basic instructions on emergency treatments of dental emergencies such as avulsion, fracture, extrusion, and intrusion that an adult can perform immediately until dental treatment can be attained.

SUMMARY

The current concepts in preventive dentistry have drastically improved since the 1960s. Dental professionals must be aware of the current dental literature in order to educate their patients on various topics in preventive dentistry. Although dental caries has declined considerably in parts of the United States due to the contribution of fluoride, dental professionals will continue to see dental caries among young dental patients.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Connie Myers Kracher, PhD, MSD

Associate Professor of Dental Education, Chair of the Department of Dental Education, and Director of the Dental Assisting Program at Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne, Indiana. She holds a PhD from Lynn University in Boca Raton, Florida, and a Master of Science in Dentistry from the Indiana University School of Dentistry in Oral Biology. Dr. Kracher is a frequent contributor to the Dental Assistant Journal and author of four ADAA courses: Sports Related Dental Injuries & Sports Dentistry, Oral Health Maintenance of Dental Implants, and Blood Pressure Guidelines and Screening Techniques.

REFERENCES

American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Statement on Athletic Mouthguards. Retrieved March 7, 2012 http://www.ada.org/1875.aspx.

American Dental Association Report. Professionally Applied Topical Fluoride: Evidence-based Clinical Recommendations. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Amer Dent. 2006;137(8):1151-1159.

American Association of Pediatric Dentistry Oral Health Policies. Policy on Prevention of Sports-related Orofacial Injuries 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2012 http://www.aapd.org.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health: Preventing Cavities, Gum Disease, Tooth Loss, and Oral Cancers. 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/.

Cobb CM. Microbes, Inflammation, Scaling and Root Planing, and the Periodontal Condition. J Dent Hyg Supplement. 2008;82(3):4-9.

Cochrane NJ, Cai F, Huq NL, et al. New Approaches to Enhanced Remineralization of Tooth Enamel. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1187-1197.

Fontana M, Zero DT. Assessing Patients’ Caries Risk. JADA. 2006;137:1231-1239.

Gibson G, Jurasic MM, Wehler CJ, et al. Supplemental Fluoride Use for Moderate and High Caries Risk Adults: a Systematic Review. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:171-184.

Harris NO, Garcia-Godoy F, Nathe CN. Primary Preventive Dentistry. 7th ed. Prentice Hall; 2009.

Kracher CM, Schmeling WS. Sports-Related Dental Injuries and Sports Dentistry. American Dental Assistants Association Continuing Education Course, 2010.

Kracher CM, Schmeling WS. Oral Health Maintenance of Dental Implants. American Dental Assistants Association Continuing Education Course, 2009.

Kracher CM. Pouring Rights. American Dental Assistants Association Continuing Education Course. 2002.

Maeda Y, Kumamoto D, Yagi K, Ikebe K. Effectiveness and Fabrication of Mouthguards. Dental Traumatology. 2009;25:556-564.

Newland JR, Meiller TF, Wynn RL, Crossley HL. Oral Soft Tissue Diseases, a Reference Manual for Diagnosis & Management. 2nd ed. Lexi-Comp Inc; 2002.

Ogden C, Kit BK, Carroll MD, et al. Consumption of Sugar Drinks in the United States 2005-2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS Data Brief 71, 2011.

Palmer, CA, Burnett DJ, Dean B. It’s More Than Just Candy: Important Relationships Between Nutrition and Oral Health. Nutrition Today. 2010;45(4):154-164.

Palmer CA. Diet and Nutrition in Oral Health. Prentice Hall; 2003.

Rergezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 5th ed. Saunders; 2008.

Reynolds EC, Cai F, Cochrane NJ, et.al. Fluoride and Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate. J Dent Res. 2008;87(344):344-348.

Stewart G, Shields BJ, Fields A, et al. Consumer Products and Activities Associated with Dental Injuries to Children Treated in United State Emergency Departments, 1990-2003. Dental Traumatology. 2009;25:399-405.

Takahashi N, Nyvad B. The Role of Bacteria in the Caries Process: Ecological Perspectives. J Dent Res. 2011;90(3):294-303.

Zero DT, Zandona AF, Vail MM, et al. Dental Caries and Pulpal Disease. Dent Clinics N Amer. 2011;55(1):29-46.

www.aidsimages.ch

www.aidsimages.ch

http://doctorspiller.com

http://doctorspiller.com

https://decs.nhgl.med.navy.mil/HOT/varnish.jpg

https://decs.nhgl.med.navy.mil/HOT/varnish.jpg