You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

The ADAA has an obligation to disseminate knowledge in the field of dentistry. Sponsorship of a continuing education program by the ADAA does not necessarily imply endorsement of a particular philosophy, product, or technique.

The word herpes evokes an emotional response from almost everyone. Eighty to ninety-five percent of the world's population has serological evidence of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1, generally orolabial herpes), which often presents itself as a "cold sore" on the lip(s). Only twenty to thirty percent of the U.S. population is seropositive for the herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2, generally genital herpes), which is considered a sexually transmitted disease.1

Add childhood chickenpox, adult shingles, infectious mononucleosis, the immunosuppressant drugs used by cancer and organ-transplant patients, along with the increasing number of immunosuppressed patients who have HIV and AIDS, and it's not hard to understand why we are now seeing a greater incidence of herpes infections.

A Common Disease in Several Forms

The most common problems are with HSV-1, HSV-2 and the varicella zoster virus (VZV), all of which are categorized as "herpes" viruses. The HSV-1, HSV-2 and VZV viruses all belong to the human herpes virus (HHV) family, which has eight categories including the Epstein Barr virus. Once a person in infected by the herpes virus, it remains for life either in the initial stage, recurrent stage, or in latency.

This family of viruses produces a wide spectrum of skin manifestations. It has been estimated that there are more than 500,000 new cases of genital herpes a year and more than 3 million cases of primary VZV infections a year in the United States. Recurrent infections with HSV and VZV are common, with the latter occurring with an increased frequency with advancing age.

Transmission of HSV-1 and HSV-2

Most adults acquire HSV-1 in childhood, usually from a kiss by a person unknowingly shedding the herpes virus. Primary infections may be manifest as severe stomatitis. (Figure 1) HSV-2 is considered a sexually transmitted disease. After the initial infection, further infections of HSV-1 and HSV-2 are usually self-limited, provoked by fever, viral infection, fatigue, menses and perhaps bright sunlight. Herpes viruses can be latent for many years, and then reactivate. These infections occur worldwide and equally in male and females. Lower socioeconomic groups are infected more often, perhaps because of crowded living conditions. Transmission of the HSV virus requires direct contact with bodily fluids containing the virus. Common infection sites for the HSV-1 virus include the oral, ocular, and respiratory mucosa, while HSV-2 generally affects the genitalia; however, the patient's sexual practices can transfer the virus from one site to another. Patients with HIV/AIDS, the elderly and those undergoing chemotherapy for cancer treatment have compromised immune systems. These immunosuppressed patients are more likely to have severe herpes infections, which may disseminate to any part of the body.2

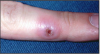

As dental professionals, it is important to remember that a fluid-filled herpetic blister is full of virus. (Figure 2) As long as the virus remains moist, it is infectious. Patients with such a blister should be rescheduled for treatment. Direct contact with lesions may spread to any site of the body, including unprotected fingers, hands and wrists. Exposure can lead to vesicle development at these sites. This particular transference of HSV-1 or 2, often affecting healthcare workers, is called herpetic whitlow. (Figure 3) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends following Standard Precautions,which includes using protective eyewear and gloves that will protect healthcare workers and patients from disease transmission.

Epidemiology of HSV-1 and HSV-2

"Fever blisters" and "cold sores" (Figure 4) are the most common presentations of HSV-1. Lesions occur on the lips and start as small grouped vesicles on a red base, progressing to ulcerated areas that heal without scarring. Lesions crust-over in four-to-five days and heal in about 10 days. Approximately 40% of patients infected with HSV-1 experience a recurrence.

HSV-2 lesions present in the same manner as HSV-1, but since HSV-2 is usually located in the genital area, it is considered a sexually transmitted disease. (Figure 5) In the United States, antibodies to HSV-2 are found in less than 1% of children under the age of 15, rise to 20% in adults between 30 and 40, and increase to about 23% in the 60- to 74-year-old age group. Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can survive briefly on open surfaces, so transmission by fomites (inanimate objects that can transmit infectious material, such as doorknobs and toilet seats) is theoretically possible but unlikely.

VZV presents as an itchy or burning area along a dermatome, an area of skin innervated by specific spinal nerves. With the VZV, a thoracic dermatome is usually affected. This follows with a painful vesicular rash that clears in about 10 days. Severe pain, which is known as postherpetic neuralgia, can remain for years, even after the lesions disappear.

Pathogenesis of HSV-1 and HSV-2

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are selective in the tissue they affect; HSV-2 replicates to a higher level in genital mucosa than does HSV-1. After HSV enters the mucous membranes, abraded skin, or the eyes, the virus enters the epithelial cells and replicates within them. The destruction of the affected cells and inflammation result in the formation of vesicles on a raised red base. The virus then spreads along sensory nerve pathways to ganglion cells (which are groups of nerve-cell bodies that lie outside of the brain), such as the trigeminal ganglion in the cervical spine in orolabial herpes or the sacral ganglion in the lower back with genital herpes. Latent infection is then established; however, the patient may still intermittently shed the virus.

Clinical HSV infection is divided into three categories: the primary first episode, the non-primary first episode and the recurrence. The primary first episode is the first clinical episode of HSV in a person who has no antibodies to HSV-1 or HSV-2. The primary first episode may be relatively severe, with systemic signs and symptoms such as fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy and lethargy. A non-primary first episode is defined as the initial clinical infection in a person who has HSV antibodies to the type that is not the cause of the current infection. This type of infection tends to be less severe than a primary first episode. Recurrence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections is generally shorter and milder than the primary episode. In about one-third of patients, the first clinical episode is the recurrence of an unidentified primary infection. Such patients have sufficient antibodies to weaken the physical outbreak, so symptoms may not be very severe.

Herpes can be diagnosed by exfoliative cytology. Culture of the virus is possible if a viral laboratory is available; however, because patients may have acquired the virus months or even years before the symptoms present, it is usually not possible to identify the source of the infection.

Tingling, burning or stinging at the site of the outbreak, the so-called prodrome, often heralds recurrent orofacial herpes. After 12 to 24 hours, small vesicles occur, and over the next two-to-three days the vesicles ulcerate and then crust. Regional lymph nodes may be swollen and tender. The lesions are not infectious when the crusts have fallen off. A patient with genital herpes may also report prodromal symptoms such as pain, tingling or itching. Female patients usually complain of malaise, dysuria, dyspareunia and leukorrhea. Examination of the patient may reveal vesicles on the cervix, perianal skin, vulva and vagina. With male patients, vesicles develop on the glans, foreskin and shaft of the penis. Ruptured vesicles appear as shallow, painful ulcers. Inguinal lymphadenopathy may be present.

HSV infections are more active and more severe in immunocompromised patients. Both primary and recurrent infections can be very severe, and one recurrence may not heal completely before the next one erupts. In addition, systemic spread is more likely in the immunocompromised patient.3

The herpes simplex virus may also cause keratitis, which is an inflammation of the cornea, or keratoconjunctivitis, which is inflammation of the cornea and conjunctiva. These HSV infections present with acute pain, blurred vision and tearing. Dendritic (branch like) ulcers, best seen with fluorescein stain under ultraviolet light, are diagnostic of this infection. Herpetic eye infections are the most common cause of corneal blinding in the United States. Urgent ophthalmologic evaluation is needed with all herpetic eye infections.

Treatment of HSV-1 and HSV-2

Anesthetic mouthwashes, such as viscous lidocaine, can decrease the pain of gingivostomatitis. Acyclovir (Zovirax®) is the drug of choice for treating HSV infections. This medication works best if started as early as possible once symptoms present. In this case, the recommended dosage of oral Acyclovir is 400 mg, taken three times-a-day for ten days.1,4

Penciclovir (Denivir®) or Acyclovir ointment is a cream developed to help reduce the pain and itching associated with cold sores if applied in the early stages. It is only used externally on the lips or face. It is never to be used in the eyes or inside of the mouth. Recommended application must follow the prescription label; usual application is approximately every 2 hours while awake.

For patients with frequent recurrences, suppressive therapy is appropriate. The standard dose of Acyclovir for suppressive therapy is 400 mg taken twice-a-day.1,4 This dosage can be taken for an indefinite period of time, although most clinicians stop the medication after one year and observe the patient. If an outbreak reoccurs, the medication is re-prescribed and the patient is rechecked after another year. This regimen prevents outbreaks in the vast majority of patients.

The Varicella Zoster Virus

The varicella zoster virus is another herpes virus that follows the pattern of the herpes simplex virus, that is, infection, latency and reactivation; however, the primary infection with the VZV is typically a case of childhood chickenpox. Recurrence of the infection is more localized and is known as herpes zoster, more commonly called shingles.

Respiratory droplets as well as direct contact with cutaneous lesions spread varicella. Chickenpox is highly contagious, rapidly spreading in areas of crowding, such as schools and daycare centers. By adulthood, more than 90% of the population has had chickenpox; reactivation in the form of herpes zoster occurs in 20% of these patients.

The medical importance of chickenpox continues to be significant; causing about 100 deaths per-year in the U.S. Neurological complications are uncommon but potentially serious. In about 1 case in 1000, encephalitis, which can be lethal, develops a few days after the appearance of the rash. More rare neurological developments include Guillain-Barré syndrome (a rapidly progressive neuropathy) and Reye's syndrome (a fatty degeneration of the liver and other viscera).

Varicella has an incubation period of 13-to-17 days. After entry into the host, the VZV replicates and spreads via the white blood cells to the skin. Further replication of the virus in the skin results in the characteristic vesicles with a red base.5

Chickenpox usually presents as an itchy, vesicular rash, usually preceded by systemic symptoms such as fever, chills and malaise. New vesicles generally stop forming in four-to-five days, and most have crusted within six-to-seven days. Patients are noncontagious and allowed to return to school or the workplace once all the lesions have crusted.

The advent of the varicella immunization, as well as many school districts requiring the immunization for school admission should decrease the number of cases, as well as the severity of complications. As reported by the CDC, before the vaccine, about 11,000 people were hospitalized each year for chickenpox. At this time, the current dose requires two immunizations and the time between is dictated by age. In children, it can be administered at 12-15 months of age and again at 4-5 years old. If the first dose is administered at 13 years old or later, the second immunization is to be administered at least one month later.

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

After chickenpox resolves, the virus is thought to remain latent in the dorsal root or cranial ganglion. In 90% of herpes zoster (HZ) cases, reactivation is presaged by pain and cutaneous sensitivity along a dermatome, usually thoracic. (Figure 6) Three-or-four days later, the lesions erupt. Over the course of several days, groups of vesicles on a red base develop along the dermatome. The vesicles then become pustular as white blood cells infiltrate to kill the virus. The pain of shingles can be severe. The principal complication of shingles is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN); the pain continues and can increase as time passes, even after the lesions have healed. A pain management specialist may have to be consulted for the treatment of PHN.

Acyclovir, 800 mg taken five times-a-day for ten days, is the recommended treatment for HZ.1,4

Famciclovir (Famvir®), 500 mg taken three times-a-day for seven days, or Valacyclovir (Valtrex®), 1000 mg taken three times-a-day for ten days, are also options.1,5 Patients with lesions involving the tip of the nose require hospitalization and consultation with an ophthalmologist. Lesions such as these imply that the trigeminal nerve is involved, which may result in corneal lesions.

A zoster immunization is also available and recommended for anyone over 60 years of age who has had chickenpox. As the virus is always in the body, the CDC recommends the immunization to reduce the risk of return. In clinical trials, the vaccine reduced the risk by 50% and reduced the painful symptoms for those who continue with bouts of shingles.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

This herpetic disease is more commonly known in the United States as infectious mononucleosis, "mono," or "the kissing disease." People can remain asymptomatic for years as they shed the infectious virus commonly found in saliva. The CDC indicates that as many as 95% of people aged 35-40 have been infected. Hunt reports online that up to 80% of college students in the United States are seropositive for EBV.

Rarely seen in the US, EBV is a causative agent for certain types of cancer (Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal cancer). Oral hairy leukoplakia is associated with EBV and those people who have become immunocompromised, such as with infectious HIV.

When the EBV is triggered into infectious mononucleosis, symptoms can range from fever, sore throat, swollen glands, malaise, and general fatigue with more extreme symptoms including inflammation of the spleen and liver. While the person can be infectious for several weeks, most individuals already exposed to EBV are not at risk when exposed. EBV remains dormant or latent in a few cells of the throat for the rest of the person's life. Periodically, the virus can reactivate and be detected in the saliva.

There is no specific treatment for infectious mononucleosis. The severity of the disease often depends on age and is usually resolved within 1-4 weeks. There are no antiviral drugs or vaccines as of this time. Those infected may take prescribed steroids to reduce swelling of the throat or tonsils and overall inflammation.

Summary

The herpes viruses continue to affect patients worldwide. The use of immunosuppressant medications, the AIDS epidemic and crowded living conditions will continue to present a challenge to our healthcare system. Although there is still no cure for any forms of herpes, vaccines are now available with the hopes of decreasing occurrences of chickenpox and shingles and their painful side effects. It is important for healthcare professionals to following standard precautions to protect against disease transmission.

Glossary

Chickenpox - common disease, most often affecting children; rash, sores, or blistering skin lesions, caused by the varicella-zoster virus.

Contagious - communicable by contact.

Cutaneous - pertaining to the skin.

Dermatome - area of skin innervated by specific spinal nerves.

Disseminate - scatter or distribute over a considerable area.

Dorsal - pertaining to, on, or situated near the back.

Dyspareunia - painful coitus experienced by women.

Dysuria - painful or difficult urination.

Encephalitis - inflammation of the brain.

Episode - an incident in a series of events.

Epithelial - layer of cells forming the epidermis of the skin; the surface layer of mucous and serous membrane.

Epstein Barr Virus - commonly known as infectious mononucleosis, or "mono, the kissing disease."

Fluorescein stain - red crystalline powder used to diagnose foreign bodies or corneal lesions in the eye.

Fomites - substances that absorb and transmit infectious material.

Ganglion - a mass of nervous tissue composed principally of nerve-cell bodies lying outside the brain or spinal cord.

Gingivostomatitis - a systemic viral disease, accompanied by signs of an acute, generalized infection with distinct clinical lesions involving the mouth and sometimes the oropharynx.

Herpes - Latin and Greek terms meaning to creep; reflects the spreading nature of the rash.

Host - the organism from which a parasite obtains its nourishment.

Immunosuppressed - a substance or condition that interferes with normal immune response.

Incubation - time between infection and the appearance of signs and symptoms.

Infiltrate - to pass into or through a substance or space.

Inguinal - pertaining to the region of the groin.

Innervate - to stimulate a part of the nerve supply of an organ.

Keratitis - inflammation of cornea.

Latent - lying hidden; time during which a disease exists without manifesting itself.

Lesion - circumscribed area of pathologically altered tissue.

Lethargy/lethargic - condition of functional torpor or sluggishness; stupor.

Leukorrhea - white or yellowish mucous discharge from the cervical canal or the vagina.

Lymphadenopathy - disease of the lymph nodes.

Malaise - discomfort, uneasiness, indisposition, often indicative of infection.

Manifest - readily perceived; obvious; give evidence of.

Menses - monthly flow of bloody fluid from the uterine mucous membrane.

Neuralgia - severe, sharp pain along the course of a nerve.

Ocular - concerning the eye or vision.

Prodrome - symptom indicative of an approaching disease.

Pustular - characterized by elevation of skin filled with lymph or pus.

Recurrences - return of symptoms after a period of quiescence.

Serological - pertaining to or the study of serum.

Seropositive - a positive reaction to serological tests.

Shingles - a reactivation of herpes zoster, usually in adults; an eruption of acute, inflammatory, herpetic vesicles on the trunk of the body along a peripheral nerve.

Stomatitis - inflammation of the mucosa lining the mouth; includes gingiva, tongue, lips, and throat.

Systemic - pertaining to a whole body rather than to one of its parts.

Trigeminal - pertaining to the trigeminus or 5th cranial nerve.

Ulcerate - to produce or become affected with an open sore or lesion of the skin or mucous membrane of the body.

Varicella (chickenpox) - an acute, highly contagious viral disease characterized by an eruption that makes its appearance in successive crops, and passes through stages of macules, papules, vesicles, and crusts.

Vesicles/vesicular - blister-like small elevation on the skin containing serous fluid.

Whitlow, Herpes - HSV-1 or 2 transferred through small wounds on the hand or wrist.

Zoster - meaning girdle; belt forming around the thorax.

References

Ohana B, Lipson M, Vered N, et al. Novel approach for specific detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 antibodies and immunoglobulin G and M antibodies. Clin Diag Lab Immun 2000;7(6):904-908.

Namvar L, Olofsson S, Bergstrom T, Lindh M. Detection of typinn Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) in mucocutaneous samples by TeqMan PCR targeting a gB segment homologous for HSV Types 1 and 2. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43(5):2058-2064.

Robert C. Genital Herpes in Young Adults: Changing Sexual Behaviors, Epidemiology and Management. Herpes 2005;12 (1):10-14.

Physician's Desk Reference, 58th Ed, 2004. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics.

Rosen T, Ablon G. Cutaneous herpes virus infection update: part 2: varicella zoster virus. Consultant 1997;3(9):2443-2455.

Additional Web resources:

Herpes Viruses, Dr. Richard Hunt, University of South Carolina School of Medicine - http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/virol/herpes.htm. Accessed: August 19, 2010.

Centers for Disease Control, Epstein-Barr Virus and Infectious Mononucleosis, http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/ebv.htm. Accessed: August 21, 2010.

Centers for Disease Control, Information about Varicella and Zoster Vaccines: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/downloads/ vis-shingles.pdf and http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/downloads/vis-varicella.pdf

Spiller, M.S. (2010) Dr Martin Spiller's Website - http://www.doctorspiller.com/cold_sores.htm. Accessed September 9, 2010.

About the Author

Joe Knight, PA

Joe Knight is a family practice Physician Assistant and a medical and science writer in Fresno, California. His medical interests include academic dentistry and sport medicine.

About the Contributing Author

Wilhemina Leeuw, MS, CDA

Wilhemina Leeuw is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Dental Education at Indiana University Purdue University, Fort Wayne. A DANB Certified Dental Assistant since 1985, she worked in private practice over twelve years before beginning her teaching career in the Dental Assisting Program at IPFW. She is very active in her local and Indiana state dental assisting organizations. Prof. Leeuw's educational background includes dental assisting - both clinical and office management, and she received her M.S. degree in Organizational Leadership and Supervision. She is also the Continuing Education Coordinator for the American Dental Assistants Association.